Historical Evidence Proves Tamil Eelam is IMPOSSIBLE — A Political Fiction and a Legal Nullity

Sri Lanka has been governed continuously by Sinhala-Buddhist monarchies for over 1,700 years, supported by advanced systems of governance, irrigation, taxation, law, and religious institutions. Despite intermittent South Indian invasions and mercenary occupations, the island has never experienced indigenous Tamil political sovereignty at any point in recorded history.

Modern claims for “Tamil Eelam” do not arise from archaeology, epigraphy, genetics, history, or international law. Instead, they are constructed from colonial administrative distortions, selective historical interpretation, political myth-making, and post-colonial separatist ideology. These claims collapse under rigorous historical and legal scrutiny.

This dossier brings together prehistoric, archaeological, historical, genetic, colonial, and international legal evidenceto establish Sri Lanka’s unitary sovereignty and to decisively refute separatist narratives.

The conclusion is unambiguous:

Tamil Eelam is historically false, legally impossible, and geopolitically dangerous.

At the same time, the ultimate purpose of this analysis is not division, but unity — to ensure that all communities live together in peace, equality, dignity, and security, while firmly rejecting separatism promoted by external actors and overseas lobbies who bear no responsibility for Sri Lanka’s long-term stability, harmony, or survival.

Critically, Tamil Eelam ideology does not genuinely serve Tamil interests.

The Eelamist movement, driven largely by overseas lobbying networks, does not seek justice, development, or security for Sri Lankan Tamils. Instead, it weaponizes Tamil identity for geopolitical objectives that ultimately undermine both Tamil welfare and Sri Lankan sovereignty.

When the Eastern Province — which was never ruled, administered, settled, or conquered by South Indian powers — is forcibly included within the Tamil Eelam claim, it automatically exposes the entire Eelam project as a political fabrication, thereby casting decisive doubt even on the northern claim itself.

If the eastern claim collapses historically and legally, the northern claim collapses by logical extension, because the ideological foundation is revealed as territorial expansionism rather than historical justice.

Evidence indicates that the strategic objective of these overseas lobbies is not Tamil self-determination, but territorial reconfiguration — specifically, the merging of Sri Lanka’s Northern and Eastern Provinces with Tamil Nadu, thereby breaking Sri Lanka’s territorial integrity.

Such a geopolitical outcome would inevitably result in external dominance over Sri Lanka’s northern and eastern regions, as these actors already rely on historical South Indian origin narratives to justify political absorption.

Once territorial fragmentation is achieved, further expansionist claims would logically follow, including over Sri Lanka’s Central Plains, where new ethnic identity constructs — such as the recent “Malayalam minority” narrative — are already emerging.

This pattern reflects a classic strategy of incremental territorial destabilization:

- Fragment sovereignty,

- Manufacture identity claims,

- Internationalize grievances,

- And progressively expand geopolitical influence.

Such a trajectory threatens not only Sri Lanka’s territorial unity but long-term regional stability, placing all communities — including Tamils — at risk.

Therefore, rejecting Tamil Eelam is not anti-Tamil.

It is a pro-peace, pro-sovereignty, pro-stability, and pro-coexistence position that protects all Sri Lankans equally.

In fact, rejecting Tamil Eelam is mostly beneficial for the Sri Lankan Tamils more than anyone else.

-

Prehistoric & Early Human Settlements

(38,000 BCE – 543 BCE)

| Era | Territory (Present-Day) | Key Notes |

| Balangoda Man / Late Stone Age (~38,000 – 28,500 BCE) | Uva, Central Highlands, Horton Plains, Kitulgala, Ratnapura | Hunter-gatherers, microlithic tools, earliest evidence of humans on the island. |

| Mesolithic / Neolithic (~10,000 – 2000 BCE) | Dry zone plains (Anuradhapura, North Central, NW), Eastern river valleys | Early agriculture, cave settlements, pottery, ritual practices, organized communities. |

| Iron Age (~1000 BCE onward) | North Central (Anuradhapura), South-West (Kalu River basin), Eastern coast | Farming, early irrigation, local chieftains; island fully populated, no “empty land”. |

Key Takeaways:

- Indigenous civilization existed across Sri Lanka long before any “founding myths.”

- Archaeology and inscriptions show organized societies with governance, agriculture, and religion.

- Genetic studies indicate modern Sinhalese directly descend from prehistoric inhabitants; Sri Lankan Tamils trace largely to later South Indian migration.

- Continuous human presence establishes long-term indigenous governance, meeting international legal standards of historical sovereignty.

-

Early Sinhala Kingdoms (543 BCE – 1215 CE)

Anuradhapura Kingdom

Total Sinhala Kings Pre-1215 CE: ~190–205 (Anuradhapura + Polonnaruwa periods)

Administrative Provinces (Not Ethnic):

| Ancient Province | Modern Equivalent |

| Rajarata | North Central + Northern |

| Ruhuna (Rohana) | Southern + Southeastern |

| Maya Rata | Western + Southwestern |

| Pihiti Rata | Northwestern |

| Digamadulla | Eastern Province |

| Malaya Rata | Central Highlands |

| Vanni | North-central frontier forests |

Evidence of Island-Wide Control:

- Centralized irrigation, taxation, and military administration.

- Buddhist monastic network across all provinces.

- Foreign invasions occurred but were temporary

- never establishing permanent Tamil sovereignty.

Key Kings:

- Pandukabhaya

- Devanampiyatissa

- Dutugemunu

- Valagamba

- Mahasena

- Dhatusena

- Aggabodhi series

- Mahinda IV

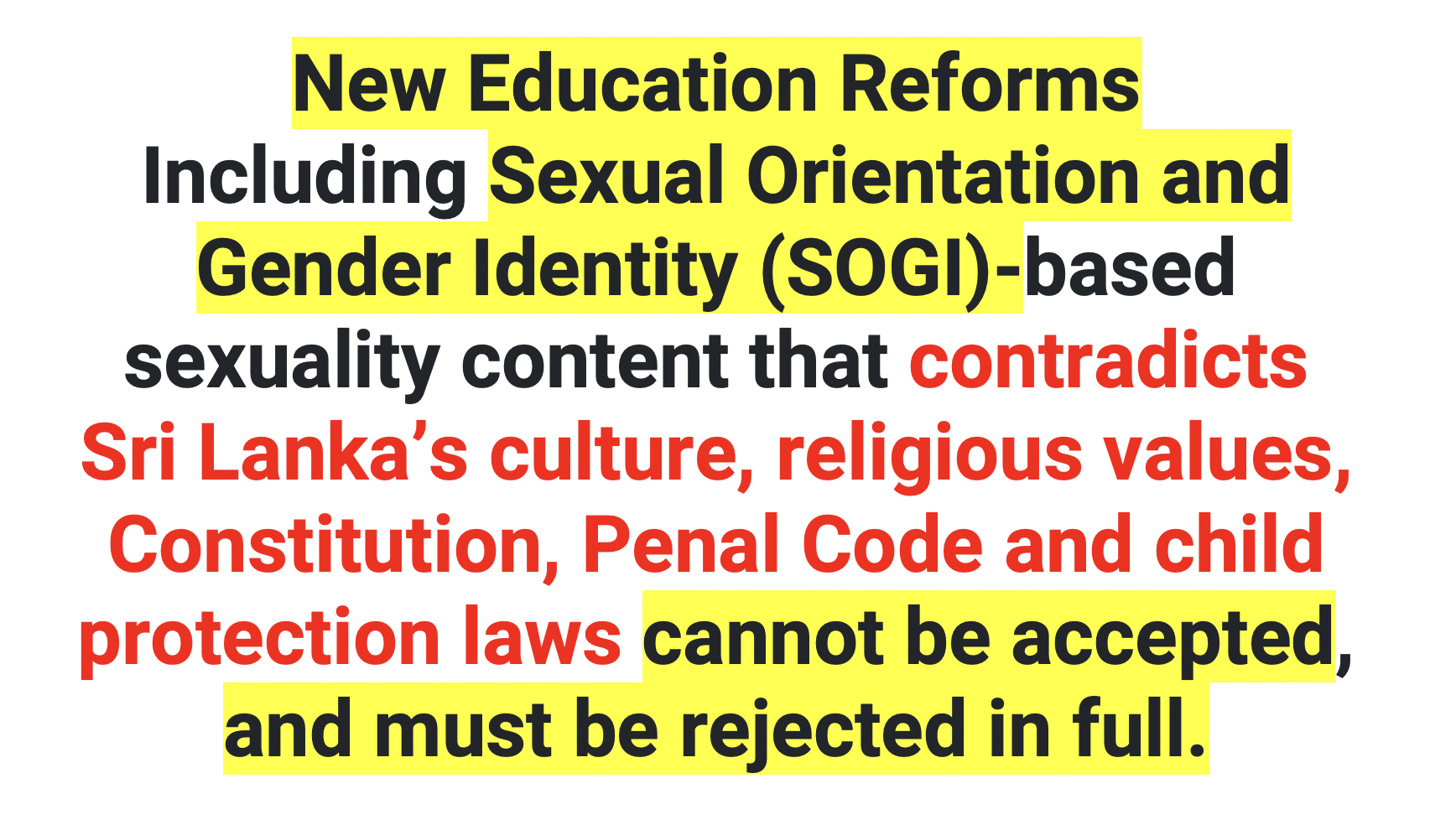

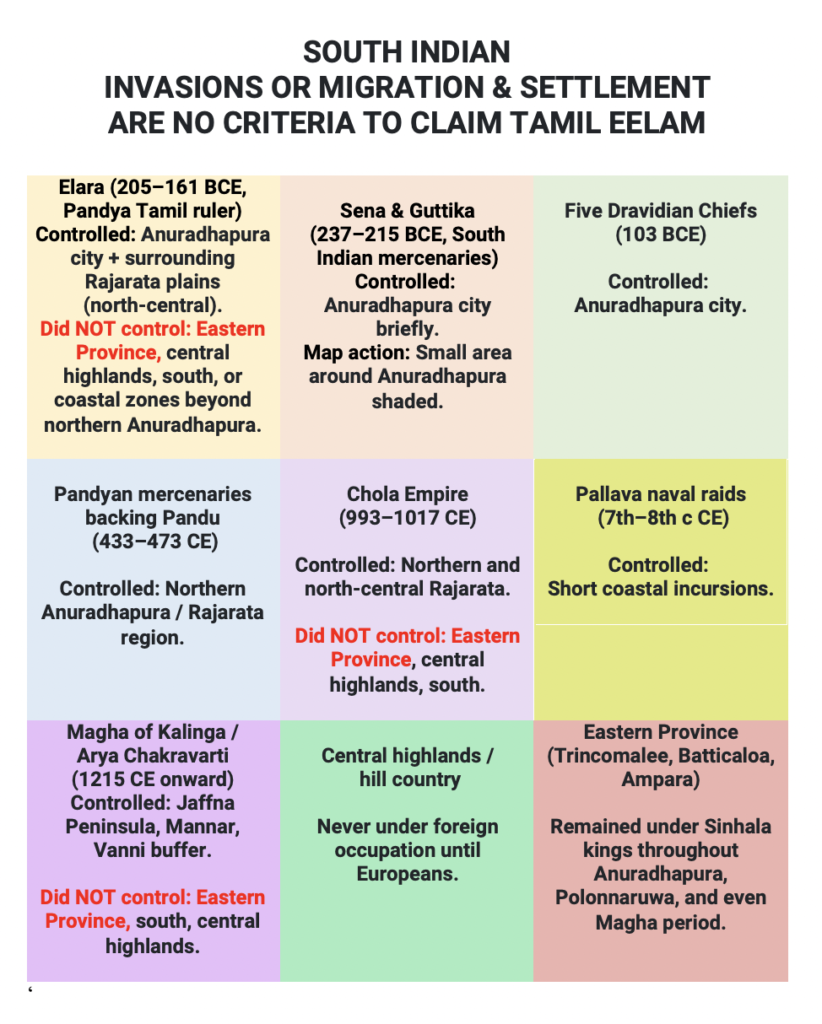

Major Foreign Occupations (Anuradhapura Era)

| Period | Invader | Duration (years) | Notes |

| 237–215 BCE | Sena & Guttika (Tamil mercenaries) | 22 | Overthrown by Prince Asela |

| 205–161 BCE | Elara (Pandya) | 44 | Defeated by Dutugemunu |

| 103 BCE | Five Dravidian Chiefs | 14 | Overthrown by Valagamba |

| 433–473 CE | Pandyan mercenaries | ~6 | Defeated by Dhatusena |

| 7th–8th c CE | Pallava naval raids | <1 | Short coastal raids, repelled |

| 993–1017 CE | Chola Empire | 24 | Partial control of northern Rajarata; expelled by Vijayabahu I |

Total 110 years South Indian occupation

INVASION STATISTICS ANURADHAPURA ERA

| Metric | Data |

| Total duration of Anuradhapura era | ~1,400 years |

| Total foreign invasions | 6 major + several minor raids (including naval raids) |

| Total years under full foreign occupation | 110 years (out of 1400 years – 110 occupied by foreign forces) |

| % of time under foreign rule | ~7.9% |

| % of time under Sinhala sovereignty | ~92.1% |

Key Insight:

- Sena Guttika was the first recorded foreign occupation in Anuradhapura, before Elara.

- Occupation ≠ Homeland; invaders never created Tamil administrative systems, provinces, or infrastructure.

- Chola empire invasion of Anuradhapura (993-1017CE) when Rajadhiraja Chola/successive Chola kings controlled northern and central Sri Lanka.

- King Vijayabahu 1 began expelling Cholas and established Polonnaruwa as new capital in 1070 CE.

-

Polonnaruwa Kingdom (1055 – 1215 CE)

After Chola Expulsion (1070 CE) Until 1215 CE

- There was no major full‑scale successful South Indian invasionthat temporarily occupied or displaced the Sinhala monarchy between Vijayabahu I’s victory and Magha’s 1215 invasion.

- Vijayabahu I expelled the Chola occupation, re‑establishing Sinhala rule by 1070 CE, and Polonnaruwa became the capital.

- Parakramabahu I (1153 – 1186 CE) strengthened the kingdom and pursued foreign campaigns fromSri Lanka — there’s no historical record of another major South Indian power occupying Sri Lanka in this era.

- The next major foreign takeoverafter the Cholas was iMagha of Kalinga in 1215 CE, whose forces invaded and seized Polonnaruwa.

Smaller South Indian Interactions

- Pandyan involvement during Queen Lilavati’s reign (1197–1198 CE)

– A Pandyan claimant momentarily deposed Lilavati and ruled for a few years — but this was not a full, lasting occupationof the kingdom like Chola (1017–1070 CE) or Magha (1215 CE). - Some evidence of Chola or South Indian raids or military pressurein the later 12th century linked to wider regional conflicts, but none resulted in long occupation or conquest of the Sinhala state.

- The Polonnaruwa kingdom remained under Sinhala sovereignty, ruled by a succession of Sinhala kings.

- Minor South Indian influence or brief incursions (e.g., Pandyan claimant to Lilavati’s throne) occurred but did not constitute occupation or a replacement of sovereignty.

- Magha of Kalinga in 1215 CE is therefore the next major foreign intrusion after the Cholas.

Capital succession after Anuradhapura & Polonnaruwa: Dambadeniya → Yapahuwa → Kurunegala → Gampola → Kotte → Kandy.

Sovereignty Restored:

- Vijayabahu I (1055–1110) expelled Cholas, restored centralized governance.

- Parakramabahu I (1153–1186) consolidated administration, irrigation, and naval power.

- Island-wide irrigation networks (Kala Wewa, Parakrama Samudra) = proof of hydraulic state sovereignty.

- Archaeological and epigraphic evidence confirms Sinhala presence across north, east, and south (Polonnaruwa, Trincomalee, Batticaloa, Jaffna).

External Confirmation:

- Faxian (5th c) & Greek geographers: single sovereign ruler of Taprobane.

- Arab traders: Sinhala kings recognized as rulers of entire island.

Key Takeaway: By 1215 CE, Sri Lanka was a unitary Sinhala-Buddhist civilization controlling the entire island.

-

Magha of Kalinga & Arya Chakravarti

(1215 CE Onwards)

| Feature | Details |

| Magha Origin | Kalinga (Odisha), East India — not Tamil |

| Force | ~24,000 mercenaries |

| Actions | Destroyed Polonnaruwa, Buddhist monasteries, irrigation networks; massacred monks |

| Outcome | Short-term occupation, limited to Rajarata; Sinhala resistance restored sovereignty |

Arya Chakravarti Dynasty in Jaffna (Post-1215 CE):

- Installed by Magha as administrators/tributaries.

- Territory: Jaffna Peninsula + fringe Vanni, parts of Mannar.

- Role: revenue collection, maritime oversight, tribute to Sinhala kings.

- Did NOT rule entire island; did not build major Hindu temple infrastructure.

- Evidence: Yalpana Vaipava Malai, Pandya inscriptions.

Key Insight: Northern Tamil administration was an imposed, limited, tributary system — not indigenous sovereignty.

-

Post-Polonnaruwa Sinhala Kingdoms (1220–1815)

| Kingdom | Period | Capital | Key Kings | Territory | Notes |

| Dambadeniya | 1220–1345 | Dambadeniya | Vijayabahu III, Parakkamabahu II | SW, Central, parts of East & North-Central | Reunited core Sinhala lands; tribute from north |

| Yapahuwa | 1272–1293 | Yapahuwa | Bhuvanaikabahu I | Central, NW, SW | Defensive capital |

| Kurunegala | 1300–1340 | Kurunegala | Bhuvanaikabahu III, Parakkamabahu IV | NW, Central, South | Consolidation of central authority |

| Gampola | 1341–1412 | Gampola | Bhuvanaikabahu IV | Central, South | Tribute maintained from Jaffna |

| Kotte | 1412–1597 | Kotte | Parakramabahu VI | SW, Central, East | Maritime trade expansion; tribute from Arya Chakravarti |

| Kandy | 1597–1815 | Kandy | Last kings | Central Highlands, parts of South-Central | Last bastion before British conquest |

Tribute System Evidence: Jaffna rulers acknowledged Sinhala kings, paying grain, elephants, and taxes.

-

Colonial Construct: Northern & Eastern Provinces

- Pre-colonial: No ethnic provinces; all administered for governance efficiency.

- British (Colebrooke–Cameron reforms, 1833):

- Northern Province = Jaffna + Mannar + Vanni (formalizing Arya Chakravarti tributary area)

- Eastern Province = Trincomalee, Batticaloa, Ampara (formerly Digamadulla under Sinhala kings)

- Implication:North & East as “Tamil homelands” = British administrative invention, not historical reality.

-

Comparative Impact: Arya Chakravarti vs Europeans

| Feature | Arya Chakravarti (1215–1505) | Europeans (1505–1948) |

| Origin | South Indian administrators | Foreign colonial powers |

| Territorial Control | Jaffna Peninsula, Mannar, Vanni fringes | Coastal forts → entire island eventually |

| Sovereignty | Tributary to Sinhala kings | Full political & military control |

| Governance | Local administration, tribute | Administrative overhaul: taxation, legal systems, plantations |

| Cultural Impact | Limited; Sinhala Buddhist culture persisted | Major cultural, religious, linguistic, economic transformation |

| Infrastructure | Minimal new hydraulic works | Some forts/ports; ancient irrigation often neglected |

| Duration | ~300 years | Portuguese: 150 yrs; Dutch: 140 yrs; British: 152 yrs |

Arya Chakravarti rule = limited tributary administration; did not replace Sinhala sovereignty.

-

Key Historical Realities

- Continuous Sinhala sovereignty:~1,758 years (543 BCE – 1215 CE) and unbroken capitals/monarchies post-1215.

- Unitary hydraulic civilization:Island-wide irrigation, Buddhist monastic network, central taxation.

- No indigenous Tamil kingdom pre-1215:Tamil presence = migrants, mercenaries, tributary administrators post-1215.

- North & East provinces = colonial constructs; Northern Tamil claims based on artificial division.

- Post-invasion north:Limited administration, no island-wide sovereignty, Sinhalese continued in hinterlands.

Sri Lanka historically functioned as a unitary Sinhala-Buddhist civilization, with sovereignty, administration, irrigation, and culture centered under Sinhala kings. Claims of an indigenous Tamil homeland prior to European colonization are unsupported by archaeology, epigraphy, chronicles, or external records.

- Genetic evidence of Tamils in the North and their civilization

- Modern genetic studies (e.g.,Bamshad et al., 2001; Silva et al., 2017) show that the Sri Lankan Tamil population is genetically close to Indian Tamils but also shows significant admixture with Sinhalese and other Sri Lankan populations.

- No evidence exists of a distinct, continuous Tamil civilization in northern Sri Lanka prior to historic South Indian invasions.

- Scientific evidence connecting South Indian Tamils with present-day Sri Lankan Tamils

- Mitochondrial DNA and Y-chromosome studies confirm aSouth Indian connection among Sri Lankan Tamils.

- Linguistically,Tamil language in Sri Lanka shows strong continuity with South Indian Tamil

- Anthropological studies indicate the bulk of Tamil settlements werepost-Anuradhapura migrations, often linked to mercenaries, laborers, or colonial plantation workers.

- Presence of Tamils before Sena & Guttika (after Anuradhapura formation)

- Historical chronicles (Mahavamsa) mentionmercenary rulers like Sena & Guttika arriving from South India.

- No evidence exists of a structured Tamil polity or autonomous Tamil rule in the North before these arrivals.

- Northern populations were predominantlySinhalese, Vedda, and minor tribal communities, according to archaeological and inscriptional evidence.

- Did Sena Guttika, Elara, Magha, Arya Chakravarti bring South Indians to settle?

- Sena & Guttika (237–215 BCE): Mercenary rulers; no record of mass settlement.

- Elara (205–161 BCE): Military ruler;Mahavamsa mentions administration but not permanent colonization.

- Magha (1215–1236 CE): Brought troops and possibly families from Kalinga and Tamil regions (Culavamsa).

- Arya Chakravarti (13th – 14th C CE, Jaffna Kingdom): Established Tamil kingdom in the North; some immigration likely, but primarily elite political families and military personnel.

Evidence: Chronicles, inscriptions, and land grants show limited migration, mostly administrative or military, not large-scale population replacement. Even if they were, it proves they were of South Indian origin not indigenous Tamils.

- Did South Indian rulers ruling Sri Lanka also rule South India?

- Sena & Guttika, Elara, Magha, Cholas: All retained power bases in South India.

- Implication:Sri Lanka was an extension of foreign conquest, not an independent Tamil polity.

- Legal argument:Self-determination requires indigenous, continuous political control, which was absent.

- Evidence of South Indian rulers ruling Eastern Province

- Elara, Cholas, Magha: Mostly controlledNorth & parts of North-Central Province.

- No evidenceof control over Eastern Province before colonial administration.

- Claims for Tamil Eelam including Eastern Province are historically baseless.

- Sinhala kings marrying South Indian Tamils

- Historical records showoccasional intermarriage for alliances, e.g., Dutugemunu’s mother or other minor alliances, but the number is small.

- Limited cultural or genetic influence; Sinhalese polity remained dominant.

- These marriages do not legitimize Tamil sovereignty claims.

- Biggest influx of South Indians came during colonial rule

- Dutch & British periods: Large-scale migration for labor, especially forcoffee, tea, and coconut plantations in Central Highlands (1820–1930).

- Many were Tamils from Tamil Nadu (estate Tamils) brought as indentured laborers.

- Proof:Colonial census data (1871, 1921), labor records, and plantation archives.

- Major Tamil presence in North & Central areas ispost-Anuradhapura, not indigenous.

- Foreign invader rule cannot justify Tamil Eelam

- International law recognizesself-determination only for indigenous peoples with historic sovereignty, not for settlers or post-conquest migrants.

- Sri Lanka’s North was never under indigenous Tamil rule; all Tamil rulers wereforeign invaders with short-term military control.

- Legal argument:No indigenous Tamil polity existed → no claim to independent state or internal self-determination.

- Questioning Indo-Lanka Accord “original habitat”

- The Accord (1987) suggested North-East as Tamil “original habitat.”-factually incorrect

- Evidence contradiction:Archaeological, inscriptional, and genetic data show Sinhalese presence predates any significant Tamil migration while Indian rulers cannot claim “original habitat”

- Therefore, Accord’s premise isfactually false.

- Additional arguments to counter Tamil Eelam claims

- Chronology of occupations:Sena & Guttika, Elara, Magha, Cholas → all temporary foreign rulers.

- Limited territorial control:Northern and North-Central only;

Eastern Province never under independent Tamil rule.

- Colonial migration:Most Tamils settled during 19th–20th C → cannot claim historic homeland.

- Sinhala sovereignty continuity:Except brief invasions, Sinhalese kings ruled uninterruptedly for 1,400+ years.

- International law:Self-determination requires indigenous continuous political authority, which historical evidence does not support for Tamils.

- Tamils were migrants, mercenaries, and colonial laborers, not an indigenous sovereign people of Sri Lanka.

- Foreign rulers’ presencedoes not equate to indigenous Tamil sovereignty.

- Northern Tamil claim, Eastern Province claim, and Tamil Eelamhave no historical or legal basis.

Legal & International Law Framework — Why Tamil Eelam Has No Legal Standing

- Uti Possidetis Juris

Territory remains with the existing sovereign state unless lawfully transferred.

→ Sri Lanka’s territorial integrity isinviolable.

- Doctrine of Effectivité (Effective Control)

Sovereignty belongs to the authority exercising continuous, stable, and legitimate governance.

→ Sinhala monarchies exercisedcontinuous island-wide governancefor over 1,700 years.

- Doctrine of Conquest (Modern International Law)

Temporary military occupation does not confer sovereignty or political legitimacy.

→ Sena–Guttika, Elara, Chola, Magha, and Arya Chakravarticannot generate self-determination rights.

- UN Charter – Article 1 (Self-Determination)

Applies to colonized or subjugated indigenous peoples with historical sovereignty.

→ Sri Lankan Tamilsdo not meet this threshold— no prior sovereign Tamil polity existed.

- International Court of Justice (ICJ) Jurisprudence

Self-determination cannot override territorial integrity of sovereign states.

→ Secession requiresexceptional conditions, none of which exist in Sri Lanka.

- Sri Lanka Citizenship Act & Constitution

→ Confirmsunitary sovereignty, indivisible territory, and equal citizenship— no legal space for ethno-territorial partition.

- Sri Lanka’sNorth and East were never indigenous Tamil homelands.

- Tamil political authority existed only asforeign occupation or tributary administration, never as sovereign statehood.

- Colonial administrative boundariescannot create legal ethnic homelands.

- Post-colonial migrationcannot generate territorial self-determination rights.

- Therefore,Tamil Eelam has ZERO standing under international law.

Responsibility of the State & Call for National Unity

Having established beyond reasonable doubt that Tamil Eelam is a fiction of political imagination unsupported by history, archaeology, genetics, or law, it becomes imperative that the Government of Sri Lanka — as:

- Custodian of the State

- Trustee of national sovereignty

- Caretaker of all citizens and resources

— ensures that all communities live together in unity, dignity, security, and equality, without permitting the creation of ethno-religious enclaves, exclusive homelands, or separatist territorial claims.

No group — whether internal political actors or external diaspora organizations operating safely from overseas — should be allowed to fracture national unity, destabilize social harmony, or resurrect divisive separatist ideologies that have already inflicted immense suffering on all communities.

Any attempt to revive ethnic territorial separatism must be firmly, lawfully, and decisively rejected.

Sri Lanka’s future lies not in ethnic division, but in mutual respect, national integration, and collective progress.

Shenali D Waduge