Road to Independence Undermined: 1977–1994 (UNP Era)

The period from 1977 to 1994 marked a decisive rupture in Sri Lanka’s post-independence trajectory. Under successive UNP governments, the State shifted away from sovereignty-centred governance toward an externally dependent, market-driven model that weakened national institutions, social cohesion, and strategic autonomy. It was a development model without planning and without taking stock of dangerous consequences that came with liberalization of the economy.

- 1977 Economic “Liberalisation” — Dependency Replaces Self-Reliance

The open-economy reforms of 1977 dismantled the import-substitution and manufacturing base built in earlier decades. Sri Lanka transitioned from a producer nation to a consumer economy reliant on foreign imports, aid, and loans.

Strategic industries were neglected or dismantled, exposing the country to balance-of-payments crises and long-term debt dependency.

Before 1977

By the mid-1970s, Sri Lanka had achieved a notable level of economic self-reliance, especially in essential goods and strategic sectors:

Manufacturing share of GDP rose steadily from about 5% in the early 1960s to over 13% by the mid-1970s, peaking at around 22% by 1977, reflecting real industrial capacity rather than trading activity.

The country locally produced a wide range of everyday necessities, reducing import dependence for:

- Clothing and textiles

- Paper and stationery

- Cement and building materials

- Food essentials and processed goods

- Household items, tyres, ceramics, glassware, and metal products

Textile self-sufficiency was a cornerstone of the economy:

- Large state-owned mills atThulhiriya, Veyangoda, and Pugoda

- A nationwidehandloom and cooperative network supplying domestic clothing needs

- Imports of textiles and garments were strictly controlled to protect local production and employment

Strategic state enterprises operated in critical sectors:

- Valachchenai Paper Millmet most national paper requirements

- Kankesanthurai Cement Factorysupplied domestic construction needs

- State corporations handledsteel fabrication, fertiliser, chemicals, and industrial inputs

- Import substitution policiesprioritised local production even when costs were higher, viewing self-reliance as a strategic necessity rather than a market inconvenience.

Foreign exchange controls ensured limited reserves were used for:

- Machinery and industrial inputs

- Medicines and essential goods

- Infrastructure development

— not consumer luxury imports.

The economy was oriented toward manufacturing, processing, and value addition, not speculative finance, mass imports, or debt-fuelled consumption.

This system prioritised resilience, employment, skill development, and national control.

What Changed After 1977

Post-1977 liberalisation dismantled foundation set pre-1977:

- Protective barriers were removed before domestic industries were strengthened

- State manufacturing capacity was neglected or dismantled

- Imports replaced local production

- Consumption replaced production

- Debt replaced self-reliance

Sri Lanka did not reform its economy in 1977 —

it abandoned an indigenous production model and entered a cycle of dependency that continues today.

Debt & Loans Before 1977 — Development Without Dependency

Before 1977, Sri Lanka did not rely on debt-driven growth.

Loans existed, but they were limited, controlled, and tied to production, not consumption.

Key characteristics of pre-1977 borrowing:

Low external debt

Sri Lanka’s foreign debt remained manageable and modest, with debt servicing consuming only a small fraction of export earnings. The country was not trapped in rollover loans or perpetual refinancing cycles.

Loans tied to productive assets

Borrowing was primarily used for:

- Industrial plants

- Manufacturing facilities

- Infrastructure (power, ports, irrigation, factories)

- State enterprises that generated output and employment

Loans were expected to pay for themselves through production, not future borrowing.

No IMF structural dependency

Sri Lanka was not governed by IMF conditionalities dictating fiscal policy, currency devaluation, subsidy removal, or market liberalisation. Economic policy remained sovereign, not externally scripted.

Strict foreign exchange controls

External borrowing was not used to finance:

- Luxury imports

- Consumer goods

- Lifestyle consumption

Foreign exchange was rationed for essentials and capital goods only.

Trade imbalances were managed, not financed by debt

When shortages occurred, the response was:

- Tighten imports

- Expand local production

- Substitute imports

— not borrow endlessly to maintain consumption.

No debt-fuelled illusion of prosperity

Growth was slow but real.

There was no artificial boom created by:

- Foreign credit

- Speculative inflows

- Currency manipulation

- Western-oriented local “experts”

The economy functioned on discipline, restraint, and production, not credit expansion.

The Turning Point After 1977

Post-1977, borrowing changed character completely:

- Loans shifted from production → consumption

- Debt financed imports instead of industries

- Balance-of-payments gaps were bridged by borrowing, not production

- Policy autonomy was surrendered to lenders and agencies

- Debt became structural, not temporary

Sri Lanka did not become indebted because it lacked resources —

it became indebted because it abandoned restraint and self-reliance.

The people were lured into a lifestyle of luxuries they could not afford — loans were taken to finance this illusion of prosperity. A small elite enjoyed excessive control and privileges, while the rest of the nation was left to foot the bills.

- Executive Presidency & the Myth of “Democratic Erosion”

The 1978 Constitution introduced the Executive Presidency to ensure strong, stable governance and to protect Sri Lanka’s sovereignty in a nation emerging from centuries of colonial manipulation and internal fracture. Its original design was deliberate — to preserve national unity, continuity of leadership, and decisional clarity in moments of crisis.

The flaw was never the Executive Presidency itself.

The damage came later — through unnecessary amendments imposed over time, often driven by internal political bargaining or external pressure seeking to weaken Sri Lanka’s sovereign safeguards.

Calls to abolish or radically alter the constitution have never been neutral. They consistently originate from forces whose objective is not democratic improvement, but dilution of the very framework that prevents fragmentation, external interference, and elite capture.

This is not coincidence — it is a pattern.

Whenever Sri Lanka asserts control over its own affairs, demands arise to “reform” or “change” the constitution. That pressure is the clearest evidence that the original constitutional design functions as a protective barrier. It is precisely because it protects the nation that it is targeted.

This is why the original constitution — including the Executive Presidency — must be retained. Weakening it is not reform. It is structural disarmament.

Notably, those calling for constitutional change rarely specify what exactly must be altered. Genuine reform would name precise clauses and propose targeted amendments. The reluctance to do so signals intent beyond transparency — and that silence itself is a red flag.

Amendments to the 1978 Constitution (1978–1994): Pros & Cons

- First Amendment (20 Nov 1978)

Shifted certain cases from the Court of Appeal to the Supreme Court.

This was a technical legal adjustment.

Limitations:

- Did not improve access to justice

- Did not reduce court delays or backlog

- Second Amendment (26 Feb 1979)

Changed procedures on resignation, expulsion, and loss of parliamentary seats.

Problems:

- Increased party control over MPs

- Weakened accountability to voters

- Third Amendment (27 Aug 1982)

Allowed a President to seek re-election after four years of the first term.

Avoided frequent elections

Problems:

- Favoured incumbents

- Expanded executive dominance

- Fourth Amendment (23 Dec 1982)

Extended the life of Parliament by six years without a general election.

Problems:

- Undermined the people’s mandate

- Set a precedent for postponing elections

- Fifth Amendment (25 Feb 1983)

Allowed by-elections if a seat could not be filled through party nomination.

Problems:

- Still favoured party systems

- Did not fully restore voter choice

- Sixth Amendment (8 Aug 1983)

Banned advocacy of separatism; required an oath to uphold territorial integrity.

Benefits:

- Defended the unitary state

- Countered separatist politics legally

Problems:

- Restricted political expression broadly

- Applied beyond armed separatism

- Seventh Amendment (4 Oct 1983)

Created new administrative districts (including Kilinochchi) and High Court Commissioners.

Benefits:

- Improved administrative reach

- Expanded judicial presence

Problems:

- Did not address deeper regional grievances

- Structural change without social reform

- Eighth Amendment (1984)

Formalised appointments of President’s Counsel.

Benefits:

- Recognised senior legal professionals

Problems:

- Increased executive discretion

- Risked politicisation of legal honours

- Ninth Amendment (1984)

Adjusted public service salary structures.

Benefits:

- Corrected pay anomalies

Problems:

- Narrow administrative fix

- No wider civil service reform

- Tenth Amendment (1986)

\Modified emergency powers.

Benefits:

- Enabled faster response during crises

Problems:

- Reduced parliamentary oversight

- Increased risk of abuse

- Eleventh Amendment (1987)

Reformed High Court and prosecution processes.

Benefits:

Improved efficiency in criminal justice

Problems:

Did not ensure prosecutorial independence

Focused on structure, not ethics

‘

- Twelfth Amendment (1987 – Not enacted)

Why it matters:

Shows Parliament resisted excessive constitutional tinkering

Confirms not all changes were blindly accepted

- Thirteenth Amendment (1987)

As a result of Indo-Lanka Accord

Amended Constitution & Unitary feature to Introduce Provincial Councils and devolution of power.

Made Tamil the official language

Problems:

- Imposed under foreign pressure

- Weakened unitary authority

- Created permanent centre–province conflict

- Failed to resolve ethnic tensions

- Fourteenth Amendment (1988)

Changed electoral rules and expanded presidential immunity.

Problems:

- Excessive presidential immunity

- Weakened voter–MP connection

- Fifteenth Amendment (1988)

Lowered electoral thresholds.

Enabled smaller parties to enter Parliament

Problems:

- Fragmented legislatures

- Reduced stable governance

- Minority parties became kingmakers

- Repealing Article 96a – abolished division of electoral districts into zones (introduced in 14th amendment)

- Amended Article 98 modified procedure for Election Commissioner to certify number of members each electoral district is entitled to return

- Amended Article 99 altering provisions related to proportional representation system reducing cut-off point for representation from 12.5% (1/8th) to 5% (1/20th).

- Amended Article 130 expanding jurisdiction of Supreme Court concerning election petitions including referendums.

- Sixteenth Amendment (1988)

Article 22.1 states that Sinhala is the language of administration in all provinces “other than the Northern & Eastern provinces”. This makes Sinhala no longer the administrative language for entire country. Tamil language has status in all 9 provinces but Sinhala language is only restricted to 7 provinces.

Under Article 22.1 public records in North & East are maintained in Tamil this automatically discriminates Sinhala-speaking citizens in the North & East.

The Proviso to Article 22.1 allows President to declare any division in a Sinhala-majority province as “bilingual” if there is sufficient Tamil minority. The same legal mechanism is unavailable for Sinhala minority.

Though Sinhala & Tamil are the languages of the Courts as per Article 24 Sinhala use is restricted in North & East.

This grievance is far greater than the hyped Official Language Act echoed even now.

The Larger Truth

The 1978 Constitution itself was not the problem.

It was designed to protect:

- National sovereignty

- Unity of the state

- Stability in governance

The weakening came from:

- Piecemeal amendments

- Externally driven reforms

- Internal political opportunism

This is why every attempt to weaken Sri Lanka begins with demands to change the Constitution.

The core document, if left intact, resists fragmentation, division, and foreign leverage.

Retention — not dismantling — is an act of national defence.

1978 to 1994

Between 1978 and 1994, at least sixteen constitutional amendments were formally enacted, most of them during the 1980s — a period marked by:

Separatist conflict and constitutional responses (e.g., 6th and 13th Amendments)

- Shifts in electoral and parliamentary structure

- Judicial and language reforms

- Presidential powers and security law adjustments

- This list doesnot include later amendments (post-1994)

- Alignment with Western Strategic Interests

Non-alignment was gradually abandoned. Sri Lanka increasingly aligned its economic and foreign policy priorities with Western institutions, donors, and geopolitical interests. Policy decisions became influenced by IMF conditionalities, foreign investors, and diplomatic pressures rather than domestic priorities.

- Ethnic Polarisation & Policy Failure

Rather than addressing legitimate grievances through inclusive political reform, the UNP era saw repeated policy miscalculations that deepened ethnic polarization. The handling of the Tamil question—combined with foreign interventions—contributed directly to the escalation of militancy and the entrenchment of separatist violence.

- Indo-Lanka Accord & Sovereignty Compromise (1987)

The Indo-Lanka Accord marked one of the gravest intrusions into Sri Lanka’s sovereignty. Signed under coercive conditions, it introduced foreign military presence and imposed constitutional changes that remain contentious. The Accord neither resolved the conflict nor protected national unity.

- Suppression of Internal Dissent

The late 1980s witnessed brutal crackdowns on southern youth uprisings, exposing a double standard in human rights enforcement. Thousands disappeared or were killed, revealing a governance culture that used force rather than reform to address dissent.

- Cultural & Educational Drift

Market-centric reforms deprioritized education as a nation-building tool. The egalitarian vision of education as a social leveller weakened, contributing to rising inequality and eroding the “Age of Talent” cultivated in earlier decades.

- Legacy of the UNP Era

By 1994, Sri Lanka emerged economically fragile, socially divided, and strategically compromised. The promise of “modernisation” had come at the cost of sovereignty, self-reliance, and social justice—forcing subsequent governments to confront crises seeded during this period.

What Sri Lanka Lost — what it gained — and what it could have become

Post 1977 transformation was not merely a policy failure but a systematic dismantling of a nation-building project.

Arguably Sri Lanka had by mid-1970s laid the foundations towards a self-reliant developmental state – prioritizing production over consumption, national capacity over foreign dependency and social equity.

True, the system was not perfect, it had resource limitations, global pressures but it was on a strategically sound path. Post-1977 lost that direction.

What Sri Lanka Lost After 1977

- Lost Economic sovereignty – the ability to determine national priorities without external coercion (IMF frameworks, donor conditionalities, debt-dependent national budgeting)

- Lost Industrial Continuity – factories, mills, manufacturing systems built over decades were dismantled/neglected or replaced by import dependency & low-value assembly activities.

- Lost Policy Autonomy – Economic planning was replaced by market ideology and short term wins with long-term repercussions.

- Lost Social Balance – Public education, health, employment were replaced by inequality, urgan concentration of wealth and elite capture.

- Lost National Discipline – Consumption culture replaced restraint, production gave way to import addictions, savings replaced credit dependence.

Three generations that built a long-term development trajectory was replaced.

What Sri Lanka gained after 1977

Sri Lanka gained temporary consumption comfort — not sustainable prosperity.

- Easier access to imported goods

- A visible rise in urban lifestyles

- Infrastructure driven by foreign loans

- Foreign-funded mega projects

- Cosmetic indicators of modernisation

Beneath this façade the structure was collapsing

- Export capacity could not match import growth

- Industries stagnated

- Debt exploded

- Trade deficits increased and became permanent

- Currency depreciation became chronic

- IMF bailouts became recurring

Open Economy did not make Sri Lanka a developed economy.

Sri Lanka became a permanently indebted consumer state.

The visible “progress” was financed, not earned.

What Sri Lanka could have become – with Patience

Had the pre-1977 production model been modernised instead of dismantled, Sri Lanka today could have become:

- South Korea– industrially diversified, technologically advancing

- Malaysia– manufacturing-driven export economy

- Vietnam– state-led industrial growth with strategic liberalisation

Sri Lanka had all the pre-requisites to be so:

• High literacy

• Strong technical education

• Disciplined public institutions

• Manufacturing foundations

• Agricultural self-sufficiency

• A skilled workforce

• Strategic geographic positioning

With planned reforms, technological upgrading, export-oriented industrial policy, and strategic protection of new industries, Sri Lanka could have become a regional manufacturing and logistics powerhouse.

Instead, Sri Lanka was converted into:

-

A consumer economy

• A debt-dependent importer

• A logistics and tourism outpost

• A labour-exporting state

Rather than exporting products, Sri Lanka exports its people.

This is not development.

This is economic displacement.

The core historical mistake – Sri Lanka’s fatal error was to confuse liberalization with development.

Development builds:

- Production capacity

- Human capital

- Strategic autonomy

- Industrial ecosystems

But liberalisation without safeguards destroys all four.

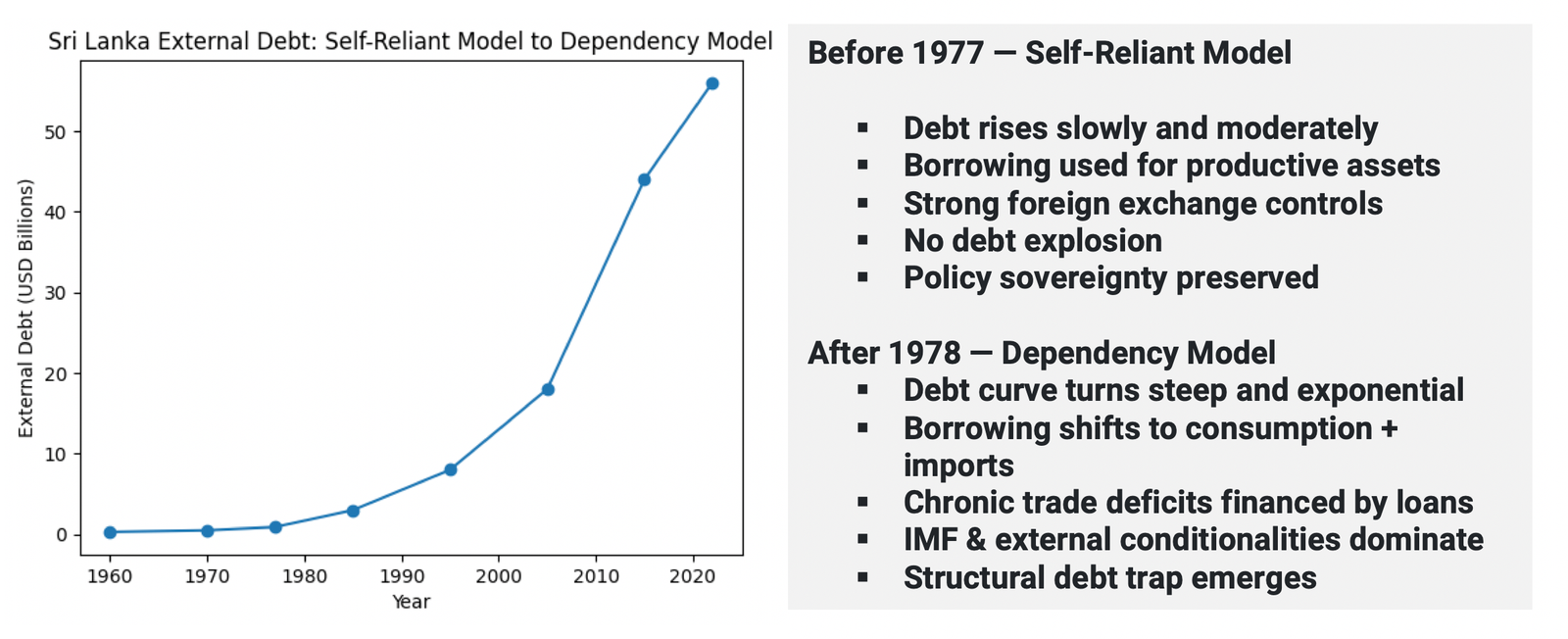

| Period | External Debt | Debt Behaviour | Development Model |

| 1960 | ~$0.3 bn | Minimal | Self-reliant |

| 1970 | ~$0.5 bn | Controlled | Production-led |

| 1977 | ~$0.9 bn | Stable & manageable | Sovereign model |

| 1985 | ~$3 bn | Rising | Import-led |

| 1995 | ~$8 bn | Accelerating | Debt-supported |

| 2005 | ~$18 bn | Structural | Dependency |

| 2015 | ~$44 bn | Explosive | Debt-trap |

| 2022 | ~$56 bn | Systemic crisis | Collapse point |

Sri Lanka’s debt curve tells the entire story: before 1977, borrowing was slow, controlled, and productive; after 1978, debt exploded exponentially — proving the shift from a sovereign development model to a structurally dependent economy.

Sri Lanka liberalised before strengthening its domestic base — a reversal of every successful East Asian development model.

This resulted in:

- Deindustrialisation

- Elite enrichment

- Debt addiction

- Policy subservience

- Strategic vulnerability

The Real Cost was not money but the possibility of what Sri Lanka could have become.

More than losing factories, policies, institutions – Sri Lanka lost its National Destiny.

- Time

- Momentum

- Generational advancement

- Strategic independence

- Even national security

Sri Lanka did not fail because it lacked intelligence, labour, or resources.

Sri Lanka failed because a functioning self-reliant development model was deliberately dismantled and replaced with a dependency-based system that served external interests and domestic elites piling debt annually to the horrific outcome that arose in 2022 with majority of people clueless to understand why Sri Lanka faced a debt debacle that had been accumulating since 1978.

Restoring sovereignty today requires more than economic reform.

It requires recovering the philosophical foundations of national development:

- Accepting need to put production before consumption

- Sovereignty before dependency

- Discipline before debt

- National interest before elite privilege

Without this clarity, Sri Lanka will remain trapped in cycles of crisis, mistaking political upheaval for national renewal. Governments will be overthrown, parties will rotate in power, and protests will erupt — yet nothing will fundamentally change — because the root ailment remains unaddressed.

That ailment lies not only with governments and opposition parties, but with the collective mindset of the people themselves.

Until the nation shifts from managing decline to building destiny, Sri Lanka will continue to rotate between anger and hope, collapse and recovery — without ever achieving structural transformation.

Shenali D Waduge