Sri Lanka’s Penal Code: Why Sections 365 and 365a exist — and why they were strengthened (not removed)

Even decades after the 1996/2006 amendments, the protections under Sections 365 and 365A remain crucial. Children continue to face sexual exploitation, grooming, and abuse, both offline and online, while even same-sex abuse victims still require clear legal pathways for justice. Narrowing or repealing these provisions would dismantle preventive tools, limit early police intervention, and reduce courts’ ability to recognize psychological trauma as legally cognizable injury.

Modern sexual predation, including digital and peer-to-peer abuse, demands a legal framework that is trauma-aware and preventive, rather than reactive.

Instead of repealing or diluting Penal Code 365/365a it should be strengthened further to include explicit recognition of online grooming, exploitation via social media, and emerging abuse patterns, ensuring that Sri Lanka’s legal protections evolve with contemporary realities while preserving the moral-based preventive, child- and victim-centred intent of Parliament.

Colonial Origin

The Penal Code was introduced in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) by the British colonial government

Key points

- Sri Lanka’s Penal Code was enacted as Ordinance No. 2 of 1883under British rule.

- It came into force on 1 January 1885.

- It replaced Roman–Dutch criminal law with a comprehensive statutory code.

- Sections 365 and 365A were part of the original Code, criminalising:

- Carnal intercourse against the order of nature (Section 365)

- Gross indecency between persons (Section 365A)

- Colonial framing was morality-based.

Crucial fact:

Independence did not result in repeal.

Parliament retained and later strengthened these provisions.

- 1995 amendment to Penal Code 365/365a (Operational in 1996)

- Clearer age-based protections

- Recognizing that sexual abuse is not limited to heterosexual acts

- Stronger penalties where children were involved

- Broader coverage of non-penetrative sexual exploitation.

- Strengthened to address child sexual abuse that did not fit classical rape definitions.

- Prevent offenders from escaping liability by arguing:

- No vaginal penetration

- Victim is male

- Act was not between a man and woman

- Sections 365/365a was strengthened in 1995 as a

- Protection to cover all provisions of sexual violence against children in particular

- Enabled early intervention before severe harm

- Covered acts that grooming laws or rape laws did not

- Higher penalties for adults (above 18) committing unnatural offences against minors (under 16)

- Mandatory imprisonment & fines for violations involving minors

Note: 1995 Parliament chose to strengthen child protection – not liberalize sexual conduct

- 2006 amendment to Penal Code 365/365a (Operational in 1996)

- Penal Code (Amendment) Act No. 16 of 2006

- Further proof that the 1885 Colonial Penal Code was continued post-independence, strengthened in 1995 and further strengthened in 2006.

- Sexual offences were made gender-neutral

- Recognized victims as “persons” not only women (covered males)

- Recognized perpetrators as “any persons” not only men (covered women)

- Acknowledged same-sex abuse existed and must be prosecuted (as before 2006 same-sex abuse victims had no clear legal path)

- Post-2006 Parliament ensured male victims, female victims, even same-sex victims were all protected

- The 2006 amendment ensured abuse covered same-sex, abuse included non-penetration, abuse involved grooming or indecent conduct.

- Parliament inserted an explanation to several sexual offence provisions & added

- “Injuries include psychological or mental trauma”.

- Courts could now

- Recognized mental/psychological harm

- Treat trauma as legally cognizable injury

- Order compensation based on that harm

- Abuse was no longer assessed only by – physical injury, penetration or visible harm.

Those who argue that 365/365a is a colonial law conveniently omit the additions done in 1995 and 2006.

Through the 1995 amendment (operational in 1996), Parliament

- Focused on child protection

- Preventive criminalization

- Recognizing same-sex abuse risks

In 2006 Parliament

- Recognized mental & psychological harm

- Victim-centred justice

- Acknowledge long-term trauma

Note:

Thus, Parliament updated the 1885, 1995 law to respond to reality not ideology.

If 365A is repealed and 365 is narrowed:

- The 2006 trauma-based compensation pathway collapses for acts previously covered

- Same-sex abuse victims must meet higher thresholds under other sections

- Preventive and victim-centric protections built over 30 years are dismantled

However, in 2023, SLPP MP Dolawatte presented a private members bill calling for the diluting of Penal Code 365 via amendment & the complete repeal of Penal Code 365a.

https://documents.gov.lk/view/bills/2023/3/305-2023_E.pdf

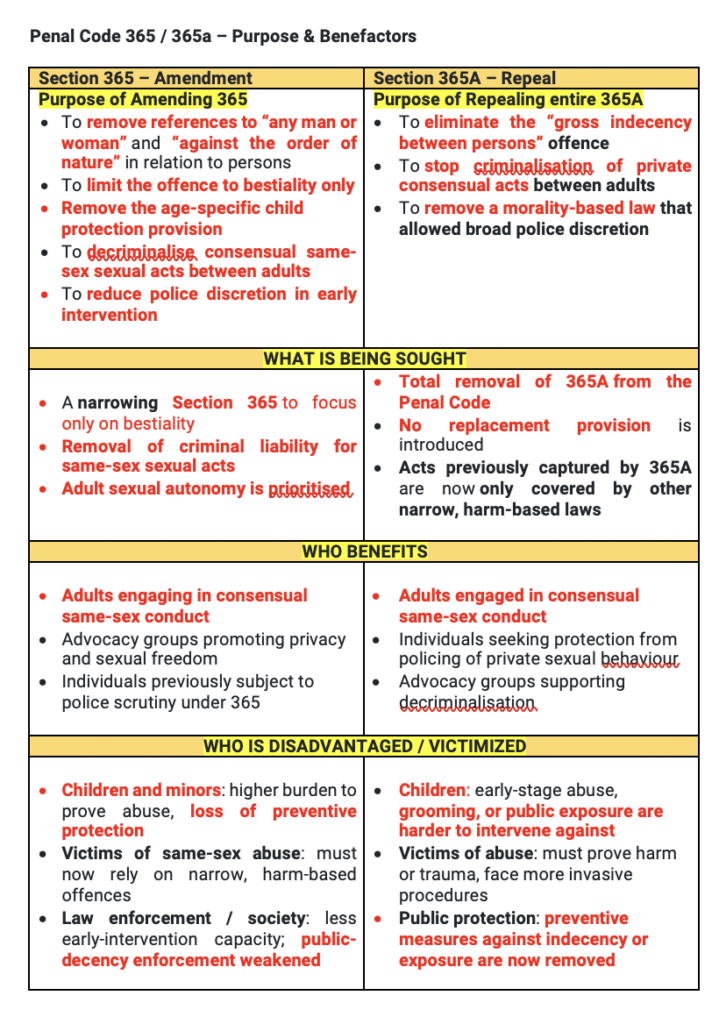

What the Private Members Bill in 2023 by MP Dolawatte sought to do

Section 365 — Amendment

Purpose

- Remove references to “any man or woman” and “against the order of nature” in relation to persons

- Limit the offenceonly to bestiality

- Remove the age-specific child protection provision

- Decriminalise consensual same-sex sexual acts between adults

- Reduce police discretion and early intervention

Section 365A — Repeal in entirety

Purpose

- Remove the offence of “gross indecency between persons”

- Eliminate the age-specific offence protecting children under 16

- Decriminalise private consensual adult acts

- Remove preventive and trauma-recognition safeguards (2006 inclusion)

- Introduceno replacement child-protection provision

What was actually being sought in 2023

- Narrowing Section 365 to bestiality alone

- Total removal of Section 365A

- Prioritisation ofadult sexual autonomy

- Transfer of all abuse cases tonarrow, harm-based offences

- Removal of preventive legal tools built over 30 years

Why did MP Dolawatte make such a request?

Who was to benefit by the Bill he presented?

Who benefits from the amendment of 365 and total repeal of 365a? — and who bears the cost

Who Benefits

- Adults engaging in consensual same-sex conduct

- Advocacy groups promoting decriminalisation

- Individuals previously subject to police scrutiny

Our next question is naturally, who becomes victimized or is impacted if the MPs request is implemented?

Who Is Disadvantaged / Victimised

Children:

- Higher burden of proof

- Loss of early-intervention safeguards

- Grooming and exposure harder to stop

- Vulnerable to online sexual predatory campaigns.

Victims of same-sex abuse:

- Forced into narrow offence categories

- Greater evidentiary and procedural trauma

- Lack of compensation for abuse

Public protection:

- Loss of public-decency and preventive tools

- Law enforcement constrained to reactive action

Who Stood With the Bill — and what they actually supported

The most revealing aspect of MP Dolawatte’s 2023 Private Member’s Bill is not merely that it was presented, but who actively intervened in court to support it.

These individuals and organisations did not merely support “decriminalisation in principle”.

They petitioned the Supreme Court in defence of a Bill that:

- Removedage-specific child protections

- Repealed offences coveringnon-penetrative sexual abuse

- Eliminatedpreventive legal tools

- Dismantledtrauma-recognition mechanisms introduced in 2006

- Offeredno replacement child-protection framework

This support was knowing, informed, and deliberate.

Many of the interveners are:

- Formerchild protection authorities

- Psychiatrists and psychologists

- Human rights commissioners

- UN officials and advisers

- Legal academics

None can plausibly claim ignorance of the consequences.

The Central Contradiction

These petitioners publicly present themselves as:

- Defenders ofchildren’s rights

- Advocates ofvictim-centred justice

- Champions ofmental health and trauma awareness

Yet they supported a Bill that:

- Raised the burden of proof for abused children

- Removed early-intervention safeguards

- Forced victims into narrower, reactive offence categories

- Undermined trauma-based compensation pathways

This is not a difference of opinion.

It is a direct contradiction between public posture and legal outcome.

Individual Petitioners — Roles Matter

The following individuals intervened in support of the Bill, not as private citizens alone, but drawing authority from their professional standing:

Individual Professional and Academic Petitioners

- Professor Savitri Goonesekere: Emeritus Professor of Law; provided the foundational human rights legal framework.

- Radhika Coomaraswamy: Former UN Under-Secretary-General; focused on global human rights standards and child protection. Chairperson of South Asians for Human Rights (SAHR) former member Constitutional Council of Sri Lanka, former UN Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women, advocate of LGBTQIA rights.

- Ambika Satkunanathan: Former HRCSL Commissioner; focused on the arbitrary use of the Penal Code.

- Ramani Muttettuwegama: Former HRCSL Commissioner and Managing Partner at Tiruchelvam Associates.

- Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu: Executive Director of Centre for Policy Alternatives

- Bhavani Fonseka: Senior Researcher and constitutional lawyer at CPA.

- Mirak Raheem: Former Commissioner at the Office on Missing Persons.

- Natasha Thiruni Jayasekera Balendra: Former Chairperson of the National Child Protection Authority.

- Yamindra Watson Perera: Integrated marketing strategist and former UNICEF advisor.

- Nirupa Irani Karunaratne: Professional human rights advocate.

- Sonali Therese Gunasekera: Director of Advocacy at FPA Sri Lanka; refuted claims that decriminalization would increase HIV risk.

- Jake Randle Oorloff: Theatre practitioner and HIV services programme officer at UNDP.

- Prabasiri Ginige: Professor in Psychiatry; documented medical evidence of transgender health in Sri Lanka.

- Chandana Kapila Ranasinghe: Former President of the Sri Lanka College of Psychiatrists.

- Gameela Samarasinghe: Professor in Psychology at the University of Colombo.

- Ananda Galappatti: Medical anthropologist and mental health professional.

- Tamara Andrea (Rosanna) Flamer-Caldera: Executive Director of EQUAL GROUND.

- P. Bhoomi Harendran: Executive Director of the National Transgender Network.

- Aritha Wickremasinghe: Equality Director at iProbono and lawyer.

- Pasan Hasitha Jayasinghe: Policy researcher and PhD candidate at UCL.

- Damith Chandimal (W.L.D.C. De Alwis Gunetilleke): Human rights defender and HRCSL Sub-Committee member.

- K.M. Thushara Manoj Kumara: Chairperson of Equite Sri Lanka.

- B. Adhil Suraj Vimukthi Bandara: Member of Equite Sri Lanka and LGBTQIA+ promoter.

- Visakesa Chandrasekeram: Senior Lecturer in Law and queer filmmaker.

- Radika Guneratne: Human rights lawyer and founder of Parivartan.

- Thenu Ranketh: Executive Director of Venasa Transgender Network.

- Hettigoda Gamage Kanthilatha: Human rights activist.

- Tush Wickramanayaka: Founder of Stop Child Cruelty Trust; provided the “Best Interests of the Child” argument.

Organizational Petitioners

- Women and Media Collective (WMC): Represented by its leadership and long-standing feminist advocates.

- EQUAL GROUND: The primary organization advocating for LGBTQIA+ rights since 2004.

- Equite Sri Lanka Trust: A specialized organization focused on grassroots queer rights.

These individuals and organisations did not merely seek decriminalisation.

They supported legal changes that removed child-specific protections without replacement.

This is not about identity orientation, private adult conduct – what they sought was far more dangerous and damaging.

We have to assess

- Which laws were targeted

- What protections were removed

- Who supported those removals and why

- Who would bear the consequences

History does not record intentions.

It records outcomes and names.

And the outcome sought in 2023 was clear:

Adult sexual autonomy was prioritised — child protection was made secondary.

History should record these names by critically analyzing what the clauses of the amendment/repeal sought & the individuals/organizations that came forward to justify.

This analysis is presented to highlight the legal and social consequences of the proposed amendments, and to encourage readers to visualize their impact on child victims, as well as on same-sex victims too.

No Member of Parliament, nor any political party, should seek to amend or repeal these critical provisions of Penal Code Sections 365 and 365A.

The extraordinary level of sustained lobbying, foreign influence, and coordinated advocacy directed at removing these clauses underscores—not diminishes—their legal necessity and protective value, especially for children and other vulnerable groups.

Shenali D Waduge