The Forgotten Discrimination: How Sinhala Speakers Became Second-Class Citizens in their own State since 1987

For over two millennia, Sinhala functioned as the language of governance, law, and administration in Sri Lanka. Colonial invasions beginning in 1505—Portuguese, Dutch, and British—systematically removed Sinhala from State institutions, courts, and administration, culminating in English as the sole administrative language. By independence in 1948, the Sinhala-speaking majority had been linguistically marginalized in their own country.

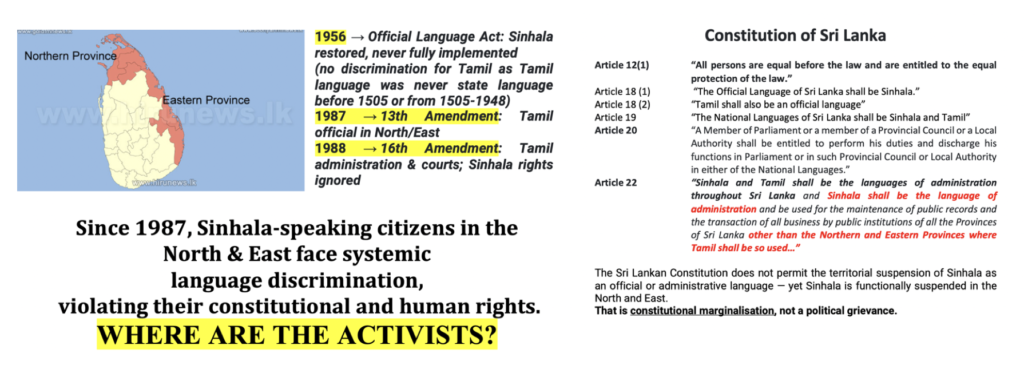

The Official Language Act of 1956 (No. 33 of 1956) restored Sinhala as the State’s official language, without removing Tamil cultural, educational, or religious rights.

However, the 13th Amendment (1987) and 16th Amendment (1988), imposed under foreign pressure, introduced territorial and asymmetrical bilingual obligations, producing systemic constitutional discrimination against Sinhala speakers in the North and East.

Historical and Indigenous Context of Sinhala in North & East

Sinhalese Communities are Indigenous

Archaeological and colonial records confirm Sinhalese villages existed in the North and East long before colonial demographic engineering.

Evidence includes:

- Medieval irrigation tanks and waterworks maintained by Sinhala villagers.

- Temples and trade routes preserved for centuries.

Dutch and British census and gazetteers (1824, 1871, 1911, 1946) identify Sinhala populations in present-day Jaffna, Trincomalee, Batticaloa, and Vavuniya.

These communities are not post-independence settlers, nor beneficiaries of state-sponsored resettlement; they are indigenous to the region.

Dutch records 1658-1796 – maps noting Sinhalese settlements in Jaffna & Trincomalee

British Census 1824 – Sinhala speaking households in North & East districts as well as Governors memos on colonizing areas with “Malabars”.

Gazetteers – mentions of irrigation tanks, temples, trade routes maintained by Sinhalese communities.

Settler Narrative vs. Indigenous Reality

- Contemporary narratives increasingly frame Sinhalese in the North/East as “recent settlers,” erasing centuries of historically documented habitation.

- By contrast, Tamil communities are being “legally recognized” as “historic inhabitants” in 13th & 16th Amendment frameworks, granting territorial language and administrative privileges.

https://www.parliament.lk/files/pdf/constitution.pdf

Constitutional Clauses Producing Discrimination

Article 12 — Equality Before the Law

Text (1978 Constitution, Article 12(1)):

“All persons are equal before the law and are entitled to the equal protection of the law.”

Problem:

- Sinhalese in Tamil-majority provinces cannot access government services in Sinhala without interpreters.

- Tamil officials in Sinhala-majority provinces are not required to learn Sinhala, creating asymmetrical obligations.

- Therefore, equality before the law is structurally violatedin these regions.

Article 22 — Official Languages

Text:

22(1): Sinhala is the official language of Sri Lanka.

22(2): Tamil may be used for administrative purposes in the North/East.

Analysis:

- Article 22(1) guarantees Sinhala as the official language nationally, but Articles 22(2) and provincial practices override it territorially.

- Sinhala-speaking citizens in the North/East are forced to operate in Tamil for courts, land records, police, and administrative services.

This is constitutional subordination of an individual right to provincial ethnic-majority preference.

Individual vs Collective Rights

- Individual language rights belong to citizens regardless of territory

- Tamil language rights under 13th & 16th amendment are collective & territorial – this violates reciprocity principle.

- Sinhalese in North and East are a minority in their own historic region without protections.

Tamil Language Status Before Colonial Rule

Historical evidence:

- Pre-1505, Sri Lanka was governed bySinhalese kingdoms (Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa, Kotte, Kandyan).

- Sinhala was the language of administration, law, diplomacy, inscriptions, and royal decrees.

- Paliwas used for religious and scholarly purposes.

- Tamil did not function as a State languagein any part of the island, nor did it hold administrative or legal authority.

During colonial rule (1505–1948):

- Portuguese, Dutch, and British introduced their own languages (Portuguese → Dutch → English).

- English became the sole language of governance, courts, and administration.

- Tamil was used locally by Tamil communities butnever enjoyed official administrative recognition anywhere in the country.

In 1956 the attempt was made to restore Sinhala language to its undeniable pre-1505 position of sole State language. A huge uproar was created for a language policy that was merely to reverse discrimination.

However, after 1987/1988 as a result of externally influenced constitutional changes Tamil replaced Sinhala in administration and courts No uproar came for the displacement of Sinhala language by the same activists and showcases their unprincipled bias.

Implication:

- The 1956 Official Language Act, restoringSinhala as the official language of the State, did not revoke any “Tamil official language” because Tamil never had such official status historically or under colonial rule (before 1505 or between 1505-1948)

- Tamil cultural and educational rights wereunaffected; the Act merely restored the historical status of Sinhala after centuries of colonial exclusion. But the narrative was framed as though it was intentionally created to discriminate Tamils which was far from the truth.

Legal and Constitutional Significance:

- Claims that the 1956 Act “discriminated” against Tamilsignore historical and legal facts.

- By contrast, the13th and 16th Amendments introduced new territorial language privileges for Tamil, creating asymmetry and marginalizing Sinhalese citizens in their own historic lands.

Note: the hypocrisy in domestic and international discourse is astounding.

Tamil advocacy is framed as human rights/justice

Sinhala disadvantage is ignored in legal, academic and international forums.

This selective application of “minority rights only” is constitutionally inconsistent with Article 12.

13th Amendment — Provincial Councils & Language

The 1987 Indo-Lanka Accord and subsequent amendment of constitution resulting in the 13th amendment & a provincial council system that impacted the unitary nature of Sri Lanka came without national debate and referendum with even foreign military presence.

The Indo-Lanka Accord, 13th & the 16th amendment gave Tamil language which had hereto never enjoyed official/state recognition official status as well as making Tamil language superior to Sinhalese in 2 of the 9 provinces.

This violated a Constitutional principle: any amendment that alters national language policy without consent may violate the democratic legitimacy of the Constitution (Articles 3, 4, 33 on sovereignty and sovereignty of the people).

Key Articles:

- Article 154B(1)(a):Provincial Councils may use Sinhala or Tamil as official languages within their jurisdiction.

- Article 154B(2):Governor may issue regulations regarding language in administration.

Discriminatory Effects:

- Territorialization of language: Tamil language dominates North/East administration.

- Asymmetric obligations: Sinhala officials must learn Tamil; Tamil officials elsewhere are not obliged to learn Sinhala.

- Individual rights to Sinhala are subordinated to provincial policy, violating Article 12.

Legal Gap:

No enforcement exists to guarantee Sinhala language service in Tamil-majority provinces.

The amendment elevates collective Tamil rights territorially, while ignoring individual Sinhalese rights or even collective Sinhalese rights.

16th Amendment — Administration & Courts

- Confirms Tamil as a language of administration and courtsin the North/East.

- Obligates Sinhala officials to function bilingually; no reciprocal obligation exists for Tamil officials elsewhere.

Result:

- Sinhalese citizens are administratively excluded in their ancestral lands.

- Dependency on translators undermines dignity and access to justice.

- Subversion of Article 22(1) national official language guarantee.

Colonial Demographics vs. Territorial Language Policy

- Colonial plantationsand labor migrations increased Tamil populations in North/East districts, but Sinhalese pre-existing populations are ignored.

- 13th & 16th Amendmentsenforce language dominance based on territorial majority, not historical indigeneity.

- Constitutional and administrative policy erases Sinhala presence, denying recognition to indigenous Sinhalese in the North and East.

Canada, India, Australia recognize internal indigenous populations to have individual and territorial rights. Sinhalese in North & East meet these criteria. But 13th & 16th amendment have ignored this.

Amendments have privileged settler narratives (colonial labor/migrations) over indigenous claims.

Individual vs. Territorial Language Rights

- International law treats language rights as individual rights attached to citizenship, not collective territorial privileges.

- Sri Lanka’s current framework:

- Tamil citizens have guaranteed territorial language privileges.

- Sinhalese citizens’ constitutional rights are conditional, creating de facto minority statusin their own historic lands.

Practical Implications:

Sinhala-speaking citizens in North/East cannot:

- Access police, courts, or land registries in Sinhala

- Engage with administration without intermediaries

- Protect property, register grievances, or exercise political rights easily

Ex:

Land registry offices in Trincomalee – Sinhala citizens must hire translators.

Police stations in Batticoloa – complaints delayed due to absence of Sinhala speaking officers.

Courts – Sinhala litigants dependent on interpreters,

Discriminatory Clauses

| Clause | Provision | Effect on Sinhalese |

| Article 12(1) | Equality before the law | Violated in North/East; must use interpreters |

| Article 22(1) | Sinhala official language | Overridden by provincial Tamil policies |

| Article 22(2) | Tamil official in North/East | Territorializes language; subordinates Sinhala rights |

| Article 154B(1)(a) & 154B(g) | Provincial Councils may use language | Sinhala officials must function bilingually; Tamil officials not reciprocally obliged

powers of provincial councils—including ability to administer and regulate official languages locally allows PCs to override national language rights. |

| 16th Amendment | Tamil as administration/court language | Sinhalese citizens administratively excluded |

- Sinhalese in the North/East are indigenous communities, predating colonial demographic engineering.

- 13th & 16th Amendmentsimpose territorial and asymmetrical language obligations, marginalizing Sinhala speakers.

- Constitutional guarantees (Articles 12, 22) are subordinated to provincial ethnic preferences, violating equality before the law.

- Recognition of Sinhalese indigeneity is critical for restoring reciprocal language rights.

- Until constitutional and administrative reforms enforce Sinhala rights equally, Sinhalese in their ancestral lands remain second-class citizens under their own State’s laws.

Equality cannot be Territorial or Selective

Sri Lanka’s language debate has been fundamentally misrepresented.

- The restoration of Sinhala in 1956 was not an act of exclusion but acorrection of a colonial injustice. Tamil had never functioned as a State or administrative language prior to colonial rule, nor was any such official status removed in 1956. What was restored was the historical and civilisational language of governance of the indigenous Sinhala people.

- By contrast, the constitutional changes introduced in 1987–1988—without referendum and under external pressure—marked an unprecedented rupture. For the first time, Sinhala-speaking citizens were renderedadministratively subordinate in parts of their own ancestral homeland, particularly in the North and East. In those provinces, Sinhala speakers are compelled to access courts, police, land administration, and public services through a language other than the State’s official language, despite constitutional recognition of Sinhala.

This arrangement constitutes systemic constitutional discrimination. It violates Article 12 (equality before the law), undermines Article 22 (official language), and contradicts the principle that sovereignty resides in the People. Language rights, if genuinely protective, must attach to citizens, not to territory, and must operate reciprocally, not asymmetrically.

- Equally grave is the erasure of Sinhala indigeneity in the North and East. Colonial censuses, gazetteers, cartography, irrigation systems, temples, and settlement records establish a continuous Sinhala presence predating demographic manipulation under colonial rule. Yet post-1987 constitutional language policy privileges territorial majorities shaped by colonial interventions while denying recognition and protection to indigenous Sinhala communities. Attempts to destroy Buddhist archaeological sites is a good example.

- The refusal—domestic and international—to recognise discrimination when it affects Sinhala speakers exposes a selective application of minority rights. Protection is asserted where it aligns with prevailing international narratives and abandoned where it would require safeguarding the majority in regionally vulnerable contexts.

A State cannot credibly uphold equality while its constitutional architecture permits citizens to be marginalised based on geography and language. Until this contradiction is addressed honestly and lawfully, Sri Lanka’s post-1987 language regime will remain not a vehicle of reconciliation, but a constitutional denial of equal citizenship.

- Sinhala speakers are citizens, not a linguistic lobby

- Their rights arise from citizenship, not population ratios

- The Constitution protects individual access to the State, not ethnic majorities

When a Sinhala citizen:

- cannot file a police complaint,

- cannot read land records,

- cannot engage courts,

- cannot deal with administration,

without translation in their own country,

the State has failed its constitutional duty.

Shenali D Waduge