Human Rights or Geopolitics? Sri Lanka Exposes the UNHRC’s Double Standards

The United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) was established in 2006 (GA Resolution 60/251) with noble intentions: to promote universality, impartiality, and cooperation protecting human rights. Yet in practice within less than 2 decades, the Council has become a political arena where blocs of states advance strategic interests, discipline weaker nations, and grant powerful allies immunity. The story of Sri Lanka shows how “human rights” has been weaponized to stifle a state for defeating its proxy terrorists.

Membership in Theory vs Reality

The Council’s 47 seats are allocated by regional quotas. In theory, every member — whether a superpower or a small state — has equal voting weight. All participate in the Universal Periodic Review (UPR), and all claim legitimacy by virtue of election through the UN General Assembly.

But in reality, membership is determined by bloc politics, donor leverage, and geopolitical bargaining.

Below is the current membership and how it behaves in practice:

UNHRC Membership 2025 – Commonalities & Contradictions

| Regional Bloc | Members (2025) | Commonalities | Differences / Contradictions | Impact on Sri Lanka |

| Africa (13 seats) | Algeria, Benin, Burundi, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Eritrea, Gambia, Ghana, Malawi, Namibia, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan | – Stress sovereignty & non-interference – Often vote as bloc – Aid/trade dependency with EU/China |

– Wide variation in rights records – Some align with West (e.g., Côte d’Ivoire) – Others shield authoritarian allies |

Despite rhetoric of sovereignty, many African votes shift under donor pressure to support Western-led resolutions on Sri Lanka |

| Asia-Pacific (13 seats) | Bangladesh, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Kyrgyzstan, Malaysia, Maldives, Nepal, Philippines, Vietnam | – Emphasize sovereignty – NAM/OIC solidarity – Defensive against external interference |

– Japan, Maldives side with West – China/India hedge for strategic reasons – Gulf states swayed by Western security ties |

Region most able to shield Sri Lanka, but divisions weaken protection |

| Eastern Europe (6 seats) | Albania, Bulgaria, Czechia, Georgia, Romania, Ukraine | – NATO/EU orientation – Consistent pro-Western alignment |

– Occasional hedges for economic ties | Predictable votes against Sri Lanka |

| Latin America & Caribbean (8 seats) | Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Mexico, Peru, Venezuela | – Tradition of rights activism – Regional solidarity mechanisms |

– Cuba/Venezuela resist politicization – Chile, Peru, Costa Rica side with EU/US |

Swing region; mixed results for Sri Lanka |

| Western Europe & Others (7 seats) | Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, UK, USA | – Move as one bloc – Fund OHCHR mandates – Champions of “accountability” |

– Minor tactical differences (e.g., Italy softer) | Principal sponsors of Sri Lanka resolutions; dominate narrative |

Commonalities that bind the Council

- All 47 claim equal legitimacy but act through blocs.

Membership is distributed regionally, yet voting and negotiations are rarely individual — states move as blocs, often dictated by donor leverage or geopolitical alignments.

- Aid and security dependencies shape decisions.

Many members’ votes are not guided by principle but by aid packages, debt relief, or military/security ties that make them beholden to powerful sponsors.

- “Universality” exists only in theory.

The Universal Periodic Review (UPR) is a mechanism applicable to all states, but in practice selective, intrusive country-specific resolutions are deployed only against targeted nations.

- Non-binding becomes binding through coercion.

Although UNHRC resolutions carry no legal force, smaller states are pressured to comply. What begins as “recommendations” often progresses into mandate overreach, forcing Charter-violating demands into national law under threat of isolation or sanctions and often for political survival.

Differences that expose contradictions

- Democracies and authoritarians sit side by side.

Liberal democracies preach rights while authoritarian states crush dissent at home — yet both claim equal authority as arbiters of others.

- Sovereignty vs intervention becomes meaningless.

Some members defend non-interference, others justify intervention. But when bloc votes are cast, principles collapse in favor of political expediency.

- Credibility crisis at the core.

States with abysmal human rights records vote to censure others. The paradox is stark: who defines “human rights” in such a forum — the violators, the perpetrators, or often both together?

Sri Lanka: A Case Study in Politicization

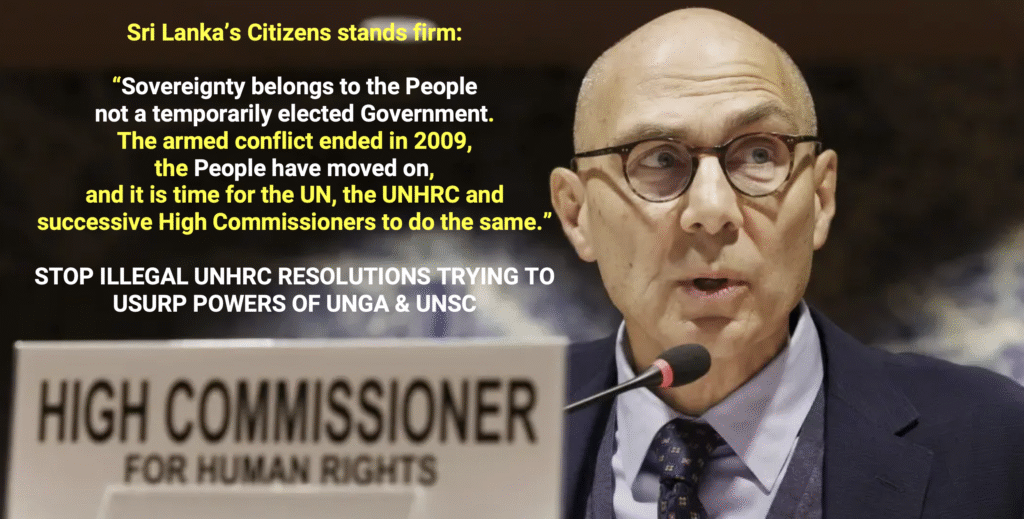

Since 2009, Sri Lanka has faced eleven intrusive resolutions in the Council. None were authorized by the UN Security Council or even the UN General Assembly. None condemned the LTTE, a terrorist group proscribed worldwide for its suicide bombings, assassinations, and child recruitment throughout 30 years of its terror campaign.

Instead, resolutions relied on leaked or contested reports — such as the Darusman Panel and the OISL — to build quasi-legal processes to which even successive UNHRC High Commissioners have been complicit undermining the Spirit of the UN Charter and the UNHRC’s original mandate. These were then institutionalized through OHCHR offices, effectively turning the HRC into a surrogate prosecutor usurping powers that were held only with the UNSC.

What is all the more alarming is that these intrusive resolutions going beyond mandate has been coerced into national law via appeasing or weak national governments (2015 Govt co-sponsored UNHRC resolution 30/1 accepting Sri Lanka’s Armed Forces committed war crimes) the current government is also seemingly falling prey by agreeing to the High Commissioners overreach demands

Examples of UNHRC’s Overreach Against Sri Lanka

- Hybrid Court / Foreign Judges:

Resolutions (notably 30/1 in 2015) demanded the creation of “special courts” with international judges, prosecutors, and investigators — a direct violation of Sri Lanka’s Constitution and sovereignty.

Several UNHRC High Commissioners have been made public statements to refer Sri Lanka to ICC though they have failed to produce any proof of 40,000 dead to claim “war crimes” or “genocide”.

- Rewriting Domestic Law:

Calls for changes in Sri Lanka’s Penal Code, Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), and other domestic security laws — an intrusion into the legislative powers of a sovereign parliament.

- Security Sector Vetting:

Pressures to “vet” and remove Sri Lankan military personnel from service and bar them from international peacekeeping roles, despite the absence of proven individual criminal responsibility.

- Land Release Demands:

Instructions on the return of land held for security reasons, ignoring Sri Lanka’s internal security assessments in post-war regions while State land cannot be granted only to one community and claims to private lands must accompany valid and verifiable proof with legitimate deeds.

- Police and Military Reform:

Recommendations to restructure Sri Lanka’s security apparatus under international guidance, effectively rewriting national defence policy.

- Devolution and Constitutional Change:

Resolutions and High Commissioner reports repeatedly pressuring for the full implementation of the 13th Amendment, indirectly imposing political settlements outside UNHRC’s scope.

- Economic Leverage:

Coupling compliance with trade benefits (e.g., GSP+ concessions tied to resolution follow-up), turning rights demands into economic blackmail.

- Cultural & Religious Impact:

The High Commissioner in his recent visit to Sri Lanka even demanded the Government legalize same-sex marriage.

Together, these show the pattern of coercion:

what began as “recommendations” turned into instructions, then into benchmarks, and finally into laws and policy reforms inside Sri Lanka — despite the fact that UNHRC resolutions are non-binding.

Contrast this with the Council’s silence on far bloodier conflicts — Iraq, Afghanistan, Yemen, Palestine. The double standard is glaring: a small state in the Global South is relentlessly targeted, while powerful states and their allies are spared scrutiny.

The selectivity is not accidental; it is structural.

One telling example was in August 2025, when the UNHRC High Commissioner flew to Sri Lanka to lay flowers at a 1990 gravesite (Chemmani) — despite DNA and carbon dating never proving whose skeletons these were, or even confirming whether they were victims of killings. This symbolic act was staged while violence raged in Gaza, where thousands of verified civilian deaths drew no equivalent gesture, no high-profile visit, and no Council resolution.

Human Rights as a Weapon

Sri Lanka’s ordeal proves that:

- Bloc politics overrides principle.

Aid and alliance pressures ensure bloc votes discipline weaker states.

- Mandate creep undermines UN structure.

The Council is inventing investigatory powers never authorized by the GA or SC.

- Selectivity destroys legitimacy.

By targeting Sri Lanka but ignoring larger conflicts, the Council exposes its bias.

- Governments, not rights violators, are stifled.

The Council has become a tool of leverage — human rights rhetoric used to enforce geopolitical compliance.

Why this matters beyond Sri Lanka?

Today it is Sri Lanka. Tomorrow it may be any state outside the protection of the Western bloc.

Africa, Asia, Latin America — all should recognize the danger of allowing the UNHRC to create precedents that erode sovereignty.

Even nations that vote against Sri Lanka may one day face the same fate themselves.

The Council was created to advance cooperation, impartiality and non-selectivity. Instead it is presiding over its own loss of credibility if it continues to weaponize human rights for political ends.

Human rights should be a shield for people, not a weapon against governments.

Sri Lanka’s experience proves the UNHRC has become precisely that weapon — and the world must not allow this precedent to stand.

UNHRC 2025 Members must analyze the Sri Lanka example carefully.

The so-called “resolutions” and High Commissioners reports/demands have gone far beyond mandate: seeking changes to Sri Lanka’s constitution, repeal of penal codes, pressing for laws that contradict the country’s cultural and religious values by demanding the legalizing of same sex marriage, dictating land ownership in favor of a single ethnic community, demonizing the Sinhalese majority, branding Sri Lanka’s military as “war criminals” without a single judicial verdict, and ridiculing the nation’s judiciary and legal system. The list goes on.

This is not accountability — it is coercion.

And once a precedent is set on Sri Lanka, no state in the Global South is safe.

The 2025 UNHRC members — whatever bloc they belong to — must recognize a simple truth: in international politics there are no permanent friends, only permanent interests. You may be a “friend” of the Western bloc today, but tomorrow you may just as easily become their enemy. Sri Lanka is the warning sign. Ignore it at your peril.

It is imperative to unite and vote against A/HRC/60/21, a resolution against Sri Lanka that exemplifies intrusive mandate overreach, violates the UN Charter, and seeks to usurp powers reserved for the Security Council — driven by a handful of Core Group nations (in this case: UK, Canada, Malawi, North Macedonia, Montenegro).

Shenali D Waduge