Online Overseas Voting: A Constitutional and National Security Risk and a Violation of Citizens Living in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka’s governments display a disturbing tendency to repeat the mistakes of other countries, even after those countries have openly admitted failure and reversed course. What is more troubling is that these reversals are not hidden or disputed — they are documented, and publicly acknowledged. Yet, despite full awareness that overseas online voting experiments failed in advanced democracies due to risks to election integrity, public trust, and national security, Sri Lanka appears willing to proceed down the same path — knowing that reversal is inevitable. Sri Lanka does not need to “learn the hard way” what others have already learned at great cost. A government that knowingly walks into a mistake — fully aware it will have to reverse —It is abdicating its constitutional duty. What is being proposed is not merely a new voting method, but a reallocation of political power from citizens living under Sri Lanka’s laws to individuals who have chosen to live outside its jurisdiction under foreign laws — without first asking the People whether they consent to such a transfer.

Sri Lanka’s Constitution (Article 3) vests sovereignty directly in the People, not to the Government of the day.

Any fundamental alteration in the exercise of political power — including how votes are cast or counted — requires the explicit consent of the People themselves (Referendum).

Lobbying, technology, or donor pressure cannot override this constitutional mandate.

If nations with stronger institutions, advanced cybersecurity capacity, and stable political environments have concluded that online voting undermines democracy, on what rational basis does a post-conflict country like Sri Lanka believe it will succeed especially when ministry websites get regularly hacked.

- What Other Democracies Learned — and Why They Reversed Course

Countries including Germany, Netherlands, Ireland, Norway, France, and the United Kingdom halted or rejected online voting after concluding that:

- Election integrity cannot be guaranteedin online environments

- The secret ballot cannot be protectedoutside controlled polling stations

- Foreign interference is undetectable and deniable

- Public confidence collapses faster than technology improves

Germany’s Constitutional Court ruled electronic voting unconstitutional, stating:

“Elections must be verifiable by the average citizen, not dependent on technical expertise.”

This principle is universal — and even more critical for Sri Lanka.

- Sri Lanka’s Constitution: Clear Safeguards, Clear Intent

Article 3 – Sovereignty of the People

Sovereignty includes:

- legislative power

- executive power

- judicial power

- the franchise

This sovereignty must be exercised in a manner that protects the State and the People.

Sovereignty belongs to the People — not to the Government of the day.

Article 3 of the Constitution vests sovereignty in the People as a collective, not in Parliament, the Executive, or the Elections Commission acting independently of the People.

Therefore, any fundamental alteration in how the franchise is exercised — especially one that shifts political power outside the territory of the Republic — requires the explicit consent of the People themselves, not merely administrative or legislative initiative.

No Government has the constitutional authority to redesign the exercise of sovereignty without consulting the sovereign — the People of Sri Lanka.

Article 4(e) – Exercise of the Franchise

The Constitution requires that the franchise be exercised at elections conducted in accordance with the law.

This has historically meant:

- controlled polling environments

- physical verification

- secrecy and transparency

- public confidence in the process

Online overseas voting transfers effective political power away from resident citizens — without their consent.

The Constitution does not authorise the Government to redefine who effectively determines electoral outcomes without the consent of the People.

Any proposal to allow large-scale overseas online voting — particularly by those who have voluntarily left Sri Lanka to live, work, or enjoy life elsewhere — must first be put to the People of Sri Lanka, whose sovereignty is directly affected.

Article 104B – Elections Commission

The Elections Commission is mandated to:

- ensurefree and fair elections

- protect theintegrity of the electoral process

- maintainpublic trust

Election Commission is not empowered to introduce mechanisms that:

- undermine Constitutional & sovereignty provisions

- cannot guarantee secrecy

- are vulnerable to foreign influence

- undermine confidence in outcomes

Any such change must be explicitly authorised by Parliament and consistent with constitutional intent.

III. Sri Lanka’s Election Law: Physical, Verifiable, Secure

Under the Parliamentary Elections Act No. 1 of 1981 and related election laws:

- Voting occurs atdesignated polling stations

- Voters are registeredby electoral district

- Ballots aresecret

- Counting isobservable and auditable

These laws were designed to:

- prevent coercion

- prevent impersonation

- ensure equality of voting power

Online overseas voting cannot meet these standards without rewriting the law — and weakening its safeguards.

- Why Sri Lanka Faces Risks Other Countries Do Not

- An Organised, Hostile Separatist Diaspora

Sri Lanka has faced:

- three decades of terrorism

- a well-documented, internationally active separatist network

- digital lobbying, fundraising, and influence campaigns abroad continue

Online overseas voting would:

- enable bloc mobilisation from abroad

- allow foreign-funded campaigning without domestic accountability

- directly influence Sri Lanka’s sovereignty and territorial integrity

No post-conflict state/Govt aware ofan unresolved separatist threat permits unrestricted overseas online voting.

- Transnational Extremist Influence

The Easter Sunday attacks demonstrated:

- ideological radicalisation from external networks

- foreign funding and influence

Online voting environments are:

- susceptible to coercion

- vulnerable to ideological pressure

- impossible to regulate across global jurisdictions

- Persistent Foreign State Interference in internal affairs

Sri Lanka has repeatedly experienced:

- diplomatic pressure

- political interference

- policy influence from external powers

Online overseas voting would:

- magnify funding and digital capability

- allow algorithm-driven influence campaigns

- disadvantage domestic candidates and voters

The result will not reflect the will of resident citizens who bear the consequences of governance.

- International Experience: Overseas Voting Practices

While the Sri Lankan Government proposes overseas online voting, global experience shows such practices are extremely rare and highly restricted.

Most countries that allow citizens abroad to vote do so via postal ballots, embassies, or proxy voting, not the internet.

Examples include:

- France: Postal or embassy voting; temporary internet voting for parliamentary elections was suspended due to security concerns.

- India: Postal ballots for government employees and armed forces abroad; no online voting.

- United States: Mail-in absentee ballots; limited internet use only for military voters.

- United Kingdom & Canada: Postal or proxy voting; no online voting for federal elections.

- Italy: Postal voting for citizens abroad.

These examples highlight that even technologically advanced and politically stable countries limit online voting for overseas citizens because of risks to ballot secrecy, voter verification, cybersecurity, and foreign influence.

Sri Lanka, with a post-conflict environment, active hostile diaspora networks, and limited digital safeguards, cannot safely implement a similar system.

The precedent is clear: overseas online voting is an exception, not the norm — and Sri Lanka’s plan would be a risky experiment with constitutional, operational, and security consequences.

- Questions That Must Be Answered — Publicly

By what constitutional authority does the Government propose to alter the exercise of the People’s sovereignty without first seeking the People’s consent?

To the Government

- Under whichconstitutional provision does the Government justify overseas online voting?

- Has Parliament approved amendments to election law permitting it?

- How will the State preventforeign funding, coercion, and cyber interference?

- Who bears responsibility if election legitimacy is challenged?

To the Elections Commission

- How will the Commission guaranteeballot secrecy in uncontrolled environments?

- How will coercion, vote-buying, and bloc voting be detected?

- How can ordinary citizensverify results, as required by democratic principle?

- Has a national security risk assessment been conducted?

To the Opposition

- Would you accept election outcomes shaped byforeign digital campaigns?

- Would you challenge results if overseas online voting determines government formation?

- Are you prepared to defend this mechanism before the Supreme Court?

To Citizens of Sri Lanka

- Should political power be exercised by thoseoutside the legal, tax, and social consequences of governance?

- Should convenience override constitutional safeguards?

- Why should online voting be granted whenany citizen may return to Sri Lanka to vote?

Citizens who retain strong civic ties to Sri Lanka, including dual citizens, are not disenfranchised.

Any citizen who wishes to exercise the franchise may do so by returning to Sri Lanka and voting within the constitutional and legal framework that applies equally to all resident voters.

The issue is not citizenship — it is method, accountability, and consent of the sovereign People.

Practical, Legal, and Public-Interest Objections to Online Overseas Voting

Beyond constitutional and national security risks, online overseas voting presents serious operational, financial, and civic failures that governments elsewhere have already identified — and rejected.

- Inherent Risks of Online Systems

Online voting suffers from the same vulnerabilities as other online platforms, including:

- hacking and cyber intrusion

- manipulation of personal data

- connectivity failures and system outages

- lack of end-to-end verifiability

Even advanced systems such as online banking and government databases experience breaches and errors.

Elections, unlike financial transactions, cannot be reversed once compromised.

- Unreliable Voter Registries and Data Integrity

Accurate voter rolls are the backbone of any credible election.

Online systems make this harder, not easier.

International experience shows:

- “ghost voters” and duplicate registrations

- voting linked to deceased persons

- non-existent individuals receiving benefits through digital systems

- widespread disputes over mailed and digitally managed voter lists

Sri Lanka lacks the capacity to:

- verify overseas voter status in real time

- cross-check deaths, migration, asylum status, or nationality changes

- audit data received from multiple foreign jurisdictions

This alone creates systemic unreliability.

- Voter Registration Will Be Costly, Complex, and Slow

Overseas online voting would require:

- new registration frameworks

- foreign-based verification processes

- constant updates across countries with different legal systems

This will be:

- expensive

- time-consuming

- administratively burdensome

Far from improving efficiency, it diverts limited state resources from domestic elections to catering to Sri Lankans living overseas who have no role in day to day governance.

- Foreign Funding and Influence Must Be Prohibited

Any attempt to implement overseas online voting will inevitably attract:

- foreign government funding & foreign intel presence

- NGO involvement

- private tech vendors

- entities with vested political or ideological interests

Allowing such funding:

- compromises sovereignty

- distorts domestic political competition

- undermines public trust

Foreign funding of electoral infrastructure should be explicitly prohibited.

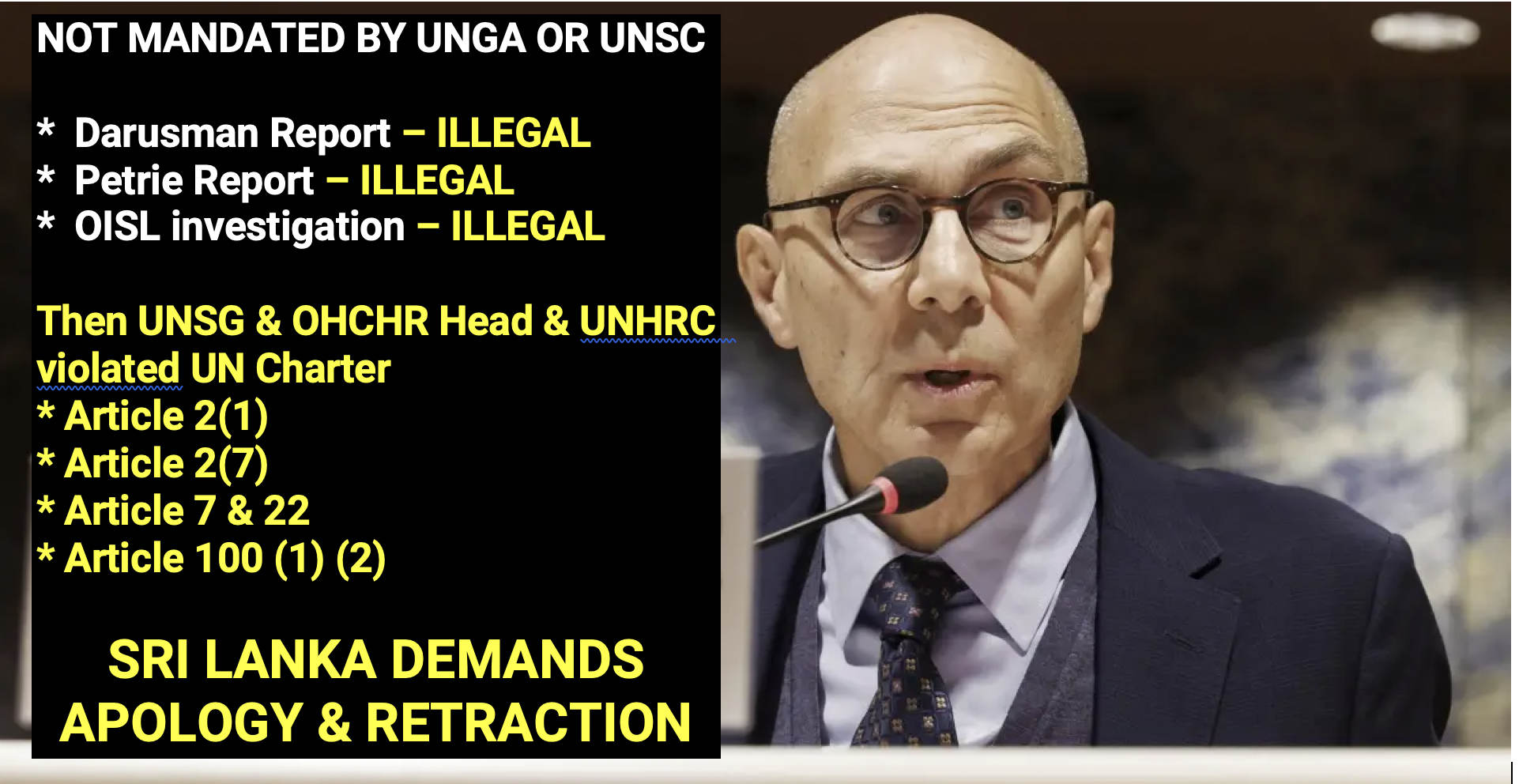

- The United Nations has no Legitimate Role

Given the UN’s deeply contested and divisive role in Sri Lanka, its involvement in electoral processes would:

- undermine public confidence

- raise sovereignty concerns

- deepen political polarisation

Election management must remain exclusively national.

- Foreign Campaigning will create chaos both in Sri Lanka & in nations where Sri Lankans live

Overseas online voting opens the door to:

- foreign-based political rallies

- fundraising events

- TV, print, and digital advertising campaigns in host countries

- These & more may stir red flags by police/intel in these countries & may even lead to revoking of citizenship (US is already mooting idea of enactments to revoke citizenship of naturalized migrants)

https://www.usa.gov/renounce-lose-citizenship

Key questions arise:

- Are Western governments prepared to police foreign election campaigns on their soil?

- Will host countries tolerate political agitation involving foreign conflicts?

- Who benefits from these campaigns — ordinary overseas citizens, or political actors and funders?

- This is also an opportunity for enemies of host countries to influence Sri Lankans which may lead to a national security threat in these host countries.

Such activity risks:

- social disruption

- communal tension

- potential violence

None of this benefits ordinary citizens abroad.

- Unsustainable Cost to the Sri Lankan Taxpayer

Sri Lanka is:

- servicing IMF obligations

- cutting social services

- managing economic recovery

Against this backdrop, online overseas voting would impose:

- technology costs

- cybersecurity expenses

- legal and monitoring costs

- foreign verification infrastructure

- massive logistics costs for even personnel to travel to different countries (opportunities for a handful of people to misuse taxpayer money)

All borne by resident taxpayers, for outcomes they may not control.

- Dual Loyalty Is Now Being Questioned Globally

Several countries, including the United States, are:

- reassessing dual citizenship

- emphasising loyalty to one country

- questioning voting in multiple jurisdictions

This global shift reinforces a basic principle:

Political power must align with civic allegiance and accountability.

Sri Lanka should not move in the opposite direction.

- Monitoring and Enforcement Is Practically Impossible

Monitoring overseas online voting would require:

- cross-border cooperation and travel by Sri Lankan officials

- enforcement in foreign jurisdictions

- oversight of coercion, funding, and interference

This is administratively unmanageable and legally unenforceable.

- Asylum Status Raises Legitimate Questions

A serious question must be asked:

Why should individuals who sought asylum abroad, often on claims against the Sri Lankan State, be permitted to influence the political future of that same State from outside its jurisdiction?

This is not about denying citizenship.

It is about protecting electoral integrity and fairness.

- The Fundamental Question Remains

Ultimately, the most important question is this:

For whose benefit is all this being done?

- Not resident citizens

- Not taxpayers

- Not electoral integrity

- Not national security

If a policy benefits external actors more than the People living within Sri Lanka, it cannot be justified as democratic reform.

Sri Lanka does not lack examples.

Countries with stronger systems tried online voting — and reversed it for valid reasons.

Sri Lanka, with greater risks, should not pretend it will succeed where others failed.

A Government that reallocates sovereign power without the consent of the People does not modernise democracy — it bypasses it.

Online overseas voting, without a mandate from the People living in Sri Lanka, is not inclusion.

It is constitutional overreach.

VII. The Global Consensus Sri Lanka Is Being Asked to Ignore

Countries that rejected online voting did not do so because they were:

- anti-technology

- anti-diaspora

- anti-democracy

They rejected it because they were:

- pro-democracy

- pro-integrity

- pro-sovereignty

- pro-constitutionalism

Sri Lanka, with far greater risks, cannot afford to be less cautious.

It is a structural change that affects:

- sovereignty

- national security

- electoral legitimacy

- constitutional order

Democracy is not measured by how easy voting becomes, but by how trustworthy the result remains.

Given that overseas online voting is constitutionally, operationally, and financially risky, why proceed with the plan?

Let us once again ask this question.

Is the decision being influenced by potential profits from technology contracts, logistics, or outcomes that benefit a handful of actors?

The decision to proceed despite clear negatives would enable a handful of actors to profit, while the People of Sri Lanka bear the costs and the risk. Any policy affecting the exercise of sovereignty must be free from conflicts of interest and guided solely by public interest, not potential personal or private gain. The Election Commission is to be held accountable for mooting idea even without legislative approvals.

Shenali D Waduge