What the UN Secretary-General, Security Council, and UNGA President must investigate in the UNHRC’s Resolutions on Sri Lanka

The United Nations Charter enshrines principles of sovereign equality, non-intervention, and adherence to mandates. Yet for over sixteen years, the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) has passed a series of resolutions on Sri Lanka that raise serious questions regarding mandate overreach, selective targeting, and non-compliance with the Charter. It is now incumbent upon the UN Secretary-General (UNSG), Security Council (UNSC) members, and the President of the UN General Assembly (UNGA) to investigate and clarify these issues to uphold the credibility of the Organization.

-

Legality of Mandates and UNHRC Actions

Issue:

The Darusman “Panel of Experts” was a personal advisory panel commissioned by UNSG Ban Ki-moon, not a UNGA or UNSC-mandated investigative body.

It was the first & only occasion a UNSG had appointed a personal advisory panel AFTER a conflict had ended. A conflict that had lasted 30 years with no resolutions passed to prevent terrorism or acted against the terrorists.

Its reports were leaked and later used as a “legal” basis for resolutions, despite UNHRC having no formal UN investigative mandate.

UN Charter Reference:

- Article 2(7) prohibits the UN from intervening in matters essentially within domestic jurisdiction.

- The UNHRC’s authority under its mandate GA 60/251of 2006 does not extend to creating binding judicial or quasi-judicial mechanisms.

Questions for Investigation:

- Did the then UNSG in 2010 exceed his authority in commissioning a private panel and allowing its findings to become basis for UNHRC resolutions?

- Was the timing — appointing the personal panel in June 2010 immediately after Sri Lanka established its domestic Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) in May 2010— consistent with the Charter’s principles of non-intervention?

- How does the then UNSG justify using leaked, extra-mandate advisory material as a de facto legal basis for resolutions?

Non-binding nature of UNHRC resolutions:

- UNHRC resolutions arenon-binding political statements, not enforceable law.

- Using such resolutions to demand prosecutions, sanctions, or hybrid tribunals exceeds the Council’s authority under the UN Charter.

Questions for Investigation:

- Why has Geneva treatedsuccessive non-binding recommendations as quasi-legal obligations for Sri Lanka?

- Does relying on UNHRC resolutions to influence domestic law or judicial processes violate the principle ofsovereign equality under Article 2(1) and non-intervention under Article 2(7)?

-

High Commissioners’ Overreach

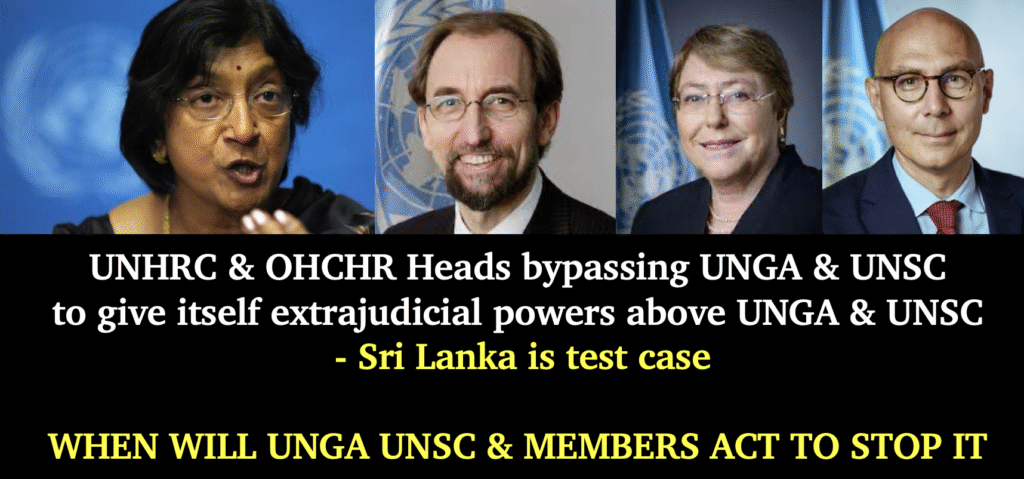

Issue: Successive High Commissioners (Pillay, Zeid, Bachelet, Türk) have publicly lobbied for outcomes beyond the OHCHR mandate, including:

- ICC-style referrals and hybrid tribunals (Pillay, Bachelet)

- Discrediting Sri Lanka’s judiciary and pushing foreign judges (Zeid)

- Prejudging grave sites without independent forensic verification, demanding same-sex marriage violating Sri Lanka’s culture & religion (Türk)

UN Charter Reference:

- Articles 1 and 2 emphasize respect for sovereign equality and domestic jurisdiction.

- No UNHRC or High Commissioner mandate exists to impose or recommend prosecutorial or judicial remedies.

Questions for Investigation:

- Did Pillay, Zeid, Bachelet, or Türk act outside their legal authority under the Charter or OHCHR mandate?

- Were conflicts of interest considered, e.g., Pillay’s Tamil heritage and repeated public political positions regarding Sri Lanka?

- Why was selective enforcement applied against Sri Lanka while similar or worse actions by US/NATO or allied states went largely unexamined?

-

Evidence, Transparency, and Due Process

Issue: UNHRC resolutions rely on:

- Anonymous testimony, sealed evidence, and leaked advisory reports

- Unverified casualty figures (e.g., 40,000 civilian deaths) without names, bodies, or forensic confirmation

- Ignoring documented LTTE crimes, missing soldiers, and civilian hostage counts – statements by then UNSG, ICRC and foreign governments calling for LTTE to release Tamil hostages.

UN Charter Reference:

- Article 1 mandates “achieving international cooperation in solving international problems” through transparency, rule of law, and accountability.

Questions for Investigation:

- How can UNHRC claim impartiality while refusing to share primary evidence for independent review?

- Were due process principles respected in relying on unverified, sealed, or anonymous material?

- Why has the UNHRC ignored the accountability of the LTTE and its international funding networks while singularly targeting a sovereign state?

-

Selective Targeting and Political Bias

Issue: Sri Lanka has faced 11 country-specific UNHRC resolutions, while far deadlier conflicts (Iraq, Libya, Gaza, Afghanistan) have not seen comparable scrutiny.

UN Charter Reference:

- Article 2(1) ensures equality of all Members before the UN.

- Article 2(7) forbids intervention in domestic matters unless authorized by the Security Council.

Questions for Investigation:

- What is the legal rationale for repeated, country-specific scrutiny of Sri Lanka?

- How much of UNHRC activity reflects geopolitics, donor influence, or selective enforcement rather than legal principle?

- Should the UNGA or UNSC review and rebalance country-specific resolutions to maintain impartiality?

Note: Initial sponsor of the Resolution (USA) has since exited UNHRC calling it a “cesspool of political bias” while ceasing all funding for investigative mechanisms against Sri Lanka clearly confirming there is no case.

Implication of non-binding resolutions:

- Despite being non-binding, repeated resolutions createpolitical pressure and narrative weight, effectively penalizing Sri Lanka without legal authority.

- This selective use amplifies the perception of wrongdoing while leaving other states largely unchallenged.

Questions for Investigation:

- How does the UNHRC justify repeated targeting of Sri Lanka usingnon-binding resolutions, while far deadlier conflicts elsewhere remain untouched?

- Does this practice reflect a pattern of political bias rather than impartial human rights monitoring?

-

Financial Oversight and the 5th Committee

Issue: Repeated Sri Lanka-specific investigations have been funded through OHCHR/OISL programmatic budgets, often without clear 5th Committee oversight.

UN Charter Reference:

- Article 17 mandates proper use of the UN budget, subject to General Assembly review.

Questions for Investigation:

- Which Member States funded Sri Lanka-specific investigations, and were political conditions attached?

- Did the UN 5th Committee exercise adequate oversight, and if not, why?

- Are extra-mandate investigations a misuse of programmatic budgets, undermining the credibility of the Organization?

-

Remedy, Sovereignty, and Closure

Issue: Calls for hybrid tribunals, ICC referral, or sanctions bypass Sri Lanka’s domestic judicial processes and undermine sovereignty.

Questions for Investigation:

- Who in Geneva possesses the legal authority to demand ICC referrals or hybrid tribunals under the UN Charter?

- How can the UNHRC ensure closure for Sri Lanka’s population, rather than allowing foreign actors to dictate terms?

- What steps will the UNSG, UNSC, and UNGA President take to restore balance, transparency, and respect for domestic jurisdiction?

-

Charter Violations, National Implementation, and Precedent Risks

- UNHRC Resolutions Are Non-Binding:All UNHRC country-specific resolutions, including those targeting Sri Lanka, are political recommendations, not legally enforceable under the UN Charter.

- National Adoption Converts Political Pressure into “Law”:When governments are pressured to implement these resolutions domestically, they effectively convert non-binding recommendations into binding law, bypassing proper legal and constitutional procedures (such was done by the regime-changed Sri Lankan govt in 2015 which co-sponsored the 30/1 UNHRC Resolution turning 7 non-binding resolutions into national law)

- Mockery of the UN Charter:This practice undermines the Charter’s provisions on state sovereignty (Article 2(1)) and non-intervention (Article 2(7)), turning the UN’s own principles on their head.

- Vulnerability of Member States:Sri Lanka’s experience illustrates how a weaker nation can be coerced into accepting politically motivated, legally questionable resolutions, making it vulnerable to international pressure and domestic instability.

- Global Governance Risk:If this precedent persist and spreads to other nations, it could weaken the authority of national constitutions worldwide, allowing external actors to dictate internal governance, and paving the way for miscreants or hostile actors to control or destabilize countries under the guise of human rights enforcement using UNHRC voting.

Questions for Investigation by UNSG, UNGA, and UNSC:

- How can the Secretary-General, Security Council, or UNGA justify pressuring Sri Lanka into implementingnon-binding resolutions as if they were legally enforceable?

- Does converting political recommendations into domestic lawviolate the UN Charter and principles of sovereignty?

- What safeguards can be introduced to prevent similar coercion against other nations, thereby protectingnational governance, rule of law, and global stability?

- How does the UN reconcile its repeated targeting of Sri Lanka with its Charter obligations totreat all Member States equally?

Upholding Charter Principles and Accountability

The UN Secretary-General, Security Council, and UNGA President have a duty to investigate the pattern of overreach, selective targeting, and use of unverified evidence in UNHRC resolutions against Sri Lanka that have continued for 16 years.

Failure to act perpetuates bias, denies closure to victims, and allows foreign powers and LTTE networks to shape narratives in violation of sovereignty.

By reviewing mandates, evidence, funding, and procedural integrity, the UN can:

- Restore credibility to the UNHRC.

- Ensure impartiality and balance in resolutions.

- Respect domestic judicial and reconciliation processes.

- Allow Sri Lankans to move forward with closure, without external interference dictating their governance or memory of history.

Only through such Charter-compliant investigations can the UN reconcile its stated principles with the reality of its actions and prevent further erosion of trust in its human rights mechanisms.

Shenali D Waduge